Quiz UK tour review – James Graham’s Coughing Major hit is back

Six years after its original premiere, the play returns to Chichester ahead of a major tour with Rory Bremnher

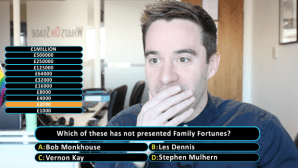

Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? may well be a modern television phenomenon with a format that has been sold to over 160 different countries worldwide, but it is the scandal of the ‘Coughing Major’ way back in 2001 that remains one of its most defining moments. James Graham’s cleverly written play about Charles Ingram’s alleged conspiratorial cheating on the show premiered here, in Chichester’s smaller Minerva space back in 2017. It went on to receive a successful West End run before being adapted for television in 2020. It now returns to Chichester once more as it begins a new national tour, but this time in the main house – where it has sadly lost much of its impact and wit along the way.

Graham’s success at weaving the recreation of the TV show into the subsequent court hearing that would eventually find Ingram and his wife, Diana, guilty of deception, is slickly structured. With a first act that proffers the case of the prosecution and the second act, the defence, Graham simultaneously skims across the judicial system and moreover the perils of the modern world’s increasing infatuation with the trial-by-media mentality that we are seeing throughout society.

Daniel Evans’ original production in the much smaller studio space felt tense and high-tech. We could easily have been sat in the Millionaire studio, with its interactive voting (of Ingram’s guilt or otherwise) making it emboldening and fast paced. Evans – on a brief return to Chichester following his recent departure to take the reigns at the RSC – once again directs, this time alongside Sean Linnen. Robert Jones’ stage design along with Ryan Day’s lighting remains blandly monochromatic throughout and is focussed more on the courtroom than the TV studio, the result being an odd detachment of the action between stage and audience.

We, the audience, as the “Common Jurors” still get the opportunity to give our own verdicts on the conspiracy via our electronic keypads, and this is where Graham’s writing superbly lays out the opposing arguments, before sitting back to see how easily the ‘jury’ can be manipulated one way of the other. In that, this is a fascinating exploration of justice and the pliability of public opinion.

Rory Bremner steps into the host’s hotseat as Chris Tarrant. It’s all-out impression work that is, as you would expect from Bremner, perfectly observed and wonderfully done – but results in comic superficiality rather than in-depth character work. Lewis Reeves brings a nicely measured affability to his Charles Ingram whilst Charley Webb is a nicely poised Diana Ingram. Mark Benton appears to have a ball as he whips through an array of different comic peripheral parts with a confidence that is not always visible elsewhere in the company. Sukh Ojla is equally fun to watch with some nicely timed facial expressions as a production assistant.

There are tantalising titbits of discussion that are sadly never fully realised in Graham’s text. He talks of confirmation bias – “say it long enough and loud enough, it becomes fact” – and there is brief exploration of the pressure that comes from trial by media as images of Dr David Kelly pop up on the large TV screens alongside Sadam Hussein. The advent of social media since 2001 makes this ever more a hot topic, of course. Ingram recognises that “viewing figures require suspense”, and whilst this is a perfectly entertaining supposition of what went on over 20 years ago, this time around it all rather lacks dramatic tension or comic bite.