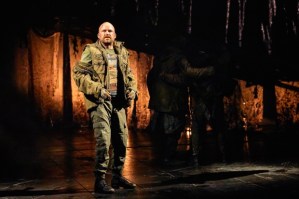

Review: Consent (Harold Pinter Theatre)

Nina Raine’s play transfers into the West End after a run at the National Theatre

© Johan Persson

Nina Raine's Consent is a coruscatingly clever play, shooting its sparks of wit and insight into many directions at once. When it opened at the National Theatre, its short run and the fact that there were so many good new plays opening at the same time last year, kept it off the prize lists. But it was always a contender, so it's good to see it in a West End transfer, where an almost entirely changed cast and a shifting social climate, which now encompasses the #MeToo movement, allows us to look at it in a new light.

Part of its brilliance is to take the emotion of Greek tragedy – the primal feelings that make women kill their children in revenge for the wrongdoings of their husband, or men to slaughter their daughters to win a battle – and place them within the apparently civilised setting of the lives of a group of well-to-do lawyers living in houses furnished by John Lewis light-fittings (brilliant, simple design by Hildegard Bechtler) and brightly coloured children's nursery furniture.

This is a world where the prosecco flows and even the most savage arguments are interrupted by a quick check that someone has bought a parking ticket. It is both blackly comic and keenly devastating in the ethical and legalistic complexities it reveals.

The opening sets the tone. Kitty (Claudie Blakley) and Edward (Stephen Campbell Moore) are celebrating the arrival of a new baby (on stage, and impossibly tiny) with their best friends Jake (Adam James) and Rachel (Sian Clifford). All bar Kitty are lawyers and they refer to themselves as their clients, as in "I'm doing a lot of raping." More accurately, the preeningly self-assured Edward is defending a man accused of raping a troubled woman, called Gayle, in a case prosecuted by another friend, the hapless and socially inadequate Tim (Lee Ingleby). In cross-examination, he destroys her story and her character.

The scenes in which Heather Craney's confused Gayle – "who is representing me?" – attempts to describe what happened while pinioned within the grasp of a legal system that regularly confuses truth with articulacy and consistency are properly upsetting. Throughout the play, Raine is conscious of the way in which women struggle to be believed and to be taken seriously. "If Lear were a woman everyone would say it's her hormones," Rachel remarks, tartly.

But the great virtue of Consent is that it doesn't concentrate on a single issue, or on a dissection of the legal system. What Raine goes on to show is that these clever lawyers, who use words as protection and weapons, entirely lack insight when it comes to their own lives, which are as messy and intractable as the lives of others they dare to judge.

The writing is incredibly sharp and always funny. "You have this fantasy that someone loves you for yourself," says Jake. "That's your mother," shoots back Rachel. But it is also compassionate; the difficulties of truth in love and life are laid bare and no-one is immune from the chaos, the gaping maw of the unknown that passion arouses.

There are issues, I think, over Raine's handling of the working-class character of Gayle, who, even in Craney's heartfelt performance, we know far less well than the other protagonists. But it is also true that the scenes in which she appears cut to the heart, revealing the law's moral bankruptcy. The introduction of Zara (Clare Foster), an actress longing for a baby, is perhaps a plot thread too far.

But I admire the way Raine is so even-handed in her treatment of character and theme. In the play's closing canter, the monstrously solipsistic Jake is revealed to have precisely the empathy that Ed so crucially lacks; at the same time, Ed's reliance on reason is gradually broken down by the strength of his own feelings, while Kitty's appeals for insight are shown to have their own limitations.

This makes it sound schematic. It's not. In fact, its vivid complexity is one of the qualities that makes Consent such an unmissable play. Under Roger Michell's assured direction, it raises questions rather than giving answers, tentatively reaching towards conclusions. The performances are equally assured, with James (one of two original cast members, with Craney) bringing both reserves of feeling and uncanny comic timing to the role of Jake, Ingleby turning Tim into more than the butt of everyone's jokes, and Campbell Moore and Blakley drawing to perfection the picture of a relationship based in complacent self-regard that unravels in front of our eyes.