Can Julius Caesar's NT Live really capture the essence of a promenade production?

As the new Bridge Theatre gears up to broadcast Nicholas Hytner’s production into cinemas, Matt Trueman considers the pros and cons of theatre live broadcasts

© Manuel Harlan

It’s almost a decade since theatre stormed the cinema. When Helen Mirren beamed from the Lyttelton stage to big screens around the country, no-one knew whether NT Live would work. "It is something of an experiment," Nicholas Hytner said at the time. The National had three more broadcasts lined up, but it was so uncertain, it hadn’t decided which shows to do. Nobody knew what sort of show – if any – would work on screen.

What was uncertain has now become standard. Since that first flicker of live footage in June 2009, there have been 65 NT Live broadcasts. Last year, there was more than one a month. The scheme’s spread beyond the National’s stages – to Donmar Warehouse and Young Vic shows, the West End and New York – and spawned copycats elsewhere: RSC Live, Kenneth Branagh Live, Oscar Wilde Live. The format has found its form. It’s built its own vocabulary.

No live-broadcast ever entirely lives up to the actual event. Theatre exists in the room.

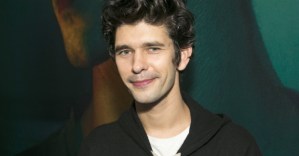

Tomorrow, almost unnoticed, live broadcast will take another leap into the unknown. The Bridge Theatre’s Julius Caesar is next on the bill. No surprise: it’s a starry Shakespeare with Ben Whishaw and David Morrissey directed by Hytner himself. What makes it unusual – and indeed, uncertain – is that Julius Caesar is a promenade production. It’s the first unconventional staging to make the jump to the screen.

Julius Caesar unfolds around its audience. It is staged in the middle of a mass of people. When David Calder’s Caesar – the spirit of one Donald J Trump – makes his first entrance, he arrives in our midst. He shakes our hands, waves our way and revels in our cheers. We’re whipped up by rock bands and geed on by stooges, we’re competed over by senators and, finally, we’re caught up in a war, smoke underfoot, flashbangs overhead. It’s thrilling and visceral. You feel it first and think it second.

© Manuel Harlan

No live-broadcast ever entirely lives up to the actual event. Even Hytner always admitted NT Live was a substitute, the next best thing to being there. It opens up access, but it’s qualitatively different. Theatre exists in the room. A cinema broadcast is something else.

The screen has, however, proved itself surprisingly adept at handling theatricality. NT Live’s house style has always been honest: pointing its cameras at a live, theatrical event, rather than reshaping a show to suit the screen. Cinema-goers know what we’re watching and read it accordingly. The form’s coped with DV8’s dance and Complicite’s stage magic, not to mention Handspring’s War Horse puppets. It can handle metaphor and theatrical imagination. It’s dealt with unusual stages – Yerma‘s glass box and the Globe with its groundlings.

Hytner casts us as Rome’s citizens, complicit in its downfall. No camera in the world can replicate that.

But promenade theatre works another way. In Julius Caesar, our presence is precisely the point. You have to be there. You’re part of it. The show makes its meaning out of its live audience. It involves us then implicates us. We’re not just watching – a camera can replicate that – we’re wrapped up in something. Hytner dissects political populism in Julius Caesar precisely by appealing to the people in the room. He casts us as Rome’s citizens and makes us complicit in its downfall. No camera in the world can replicate that.

For all it has its sceptics – I’m still a purist, but I’ll accept the benefits – NT Live has succeeded on its own terms. "The objective is greater access," Hytner said at its start, and live-broadcasts have certainly done that. Some shows have been seen by more than half a million people – an 18-month run in a single night. The question, though, has to be: Access to what?

Some shows simply can’t sit on a screen. Our presence is fundamental and necessary. We watch from within. Cameras sit outside and, in the process of being broadcast, something fundamental is lost. As the real Julius Caesar supposedly said: "Experience is the teacher of all things."

Julius Caesar broadcasts to cinemas nationwide on 22 March and runs at the Bridge Theatre until 15 April.