Review: The Real Thing (Theatre Royal Bath)

Stephen Unwin directs Tom Stoppard’s play about life imitating art

By 1982 Tom Stoppard was seen as Britain's foremost greatest living playwright with his work being played on both sides of the Atlantic to commercial and critical success. His critics, though, would talk about how all his work was cerebral, penetrating the brain but rarely stabbing at the heart. In the play he wrote that year, The Real Thing, he takes us into the life of Henry, an eminently successful playwright more known for his wit and dazzling bon mots than any psychology insight. Had Stoppard gone full-on biographical?

It's a work dense in richness, like great novels or indispensable tracks, impossible to fully get to grips with on first exposure. Henry may be a snob in his belief in the power of art, in the written word to conjure much more than simply etchings on the page, but at the same time he lays down a mantra for all of us who write in any capacity to aim higher, explore further. He is a man on the hunt for the real thing, whether in the art he creates or the love he obtains. He may be prone to agonising over his choices for Desert Island Discs, worried that his love for pop tracks is not high-brow enough, but he views life with an innocence maybe not expected of a man of letters.

For him, love is an ideal, jealousy an abstract term as he sees competitors from an intellectually lofty height. He leaves his first wife Charlotte (a portrait of marital frustration in the first act and then flirty seduction in the second in Rebecca Johnson's nuanced hands) for actress Annie, a woman who gives him the opportunity to love absolute. Yet love, like art is never that simple, pragmatism, as well as glass ceilings, are as important as each other if you want to win the game. The women are always well aware of this, it's a journey Henry has to learn through the course of the work.

That would be enough for any play but Stoppard goes further, constantly keeping us guessing as to what's real here and what isn't. It starts with a scene from one of Henry's plays, House of Cards, and then constantly links the world of the stage to what is going on behind closed doors. Is Annie having an affair with her co-star in Glasgow or are we simply watching rehearsals for Tis Pity She's A Whore? Are we watching a scene for a play that Henry has ghostwritten or witnessing a real discussion on a train? In Cards, Henry's main character is an architect and the play's architecture is constructed to perfection. Stoppard's dazzling way with plays has rarely been seen to better effect.

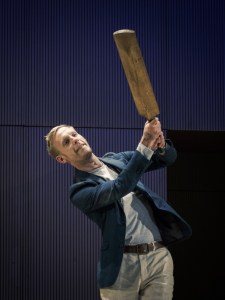

Director Stephen Unwin's work is efficient rather than revealing, while designer Jonathan Fensom delivers a set with the same clinical efficiency that Henry gets accused of, a home with all the personality of a hotel room. If Laurence Fox struggles to convince as a razor-sharp intellectual he does better once feeling is stirred into the pot in the second half. It's Flora Spencer-Longhurst though who walks away with the acting honors, her Annie is a seductive mix of playful sexuality, political idealism, and a woman always prepared to go to bat for what she wants.

Stoppard pulls off one final twist at the conclusion about her character but she shrugs this off with a dip to the face of an obnoxious talentless hanger-on and a shrug of the shoulder out of her dress. Its feminism is worth another cheer for Stoppard's great work.

The Real Thing runs at Theatre Royal Bath until 30 September then tours.