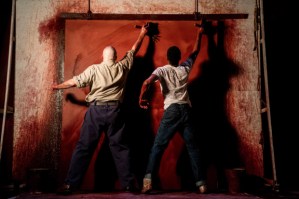

Review round-up: Did Alfred Enoch and Alfred Molina paint the town Red?

John Logan’s play comes back to London nine years after premiering at the Donmar Warehouse

© Johan Persson

Sarah Crompton, WhatsOnStage

★★★

"John Logan's play about a crisis in the life of the artist Mark Rothko has become an award-laden popular hit since it first premiered at the Donmar Warehouse in 2009. Yet the skill of Michael Grandage's production and a towering central performance by Alfred Molina cannot entirely disguise its imperfections. It's less a perceptive masterpiece and more an art history yawn."

"It is all interesting, as far as it goes, but it never really goes very far. I felt I didn't know much more about Rothko when I left than when I walked in; he becomes a series of attitudes rather than a real man."

"All the most engrossing things come from the production not the text. Christopher Oram's set, with its simulacra of Rothko's great paintings and its glorious collection of artistic clutter – buckets full of rich paint, jars of red powder, an old record player – really does pulse and throb with the pleasure of artistic creation. Neil Austin's lighting bathes it in a magical glow. Grandage's sensitive direction animates every conversation with a delicate ebb and flow."

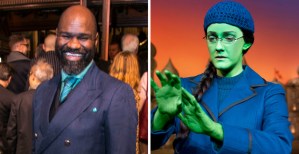

"Molina throughout is magnificent, terrifying in his rages, but profoundly moving as he touches his canvases quietly, waiting for them to speak to him. Facing a performance that has grown over the years to such a pitch of intensity and detail it is hard for Enoch to shine, but he does convince as a man struggling to make his own way, and to understand the significance of all he sees."

Ann Treneman, The Times

★★★★★

"Alfred Molina is a force of nature as Rothko: furious, intense, solid and never wavering in his belief of what it takes to be an artist. He is a visionary and a bully and he dominates the stage, even when he is just sitting there. There is also a stellar West End debut from Alfred Enoch as Ken, the student who, despite his nerves, tells his new employer that his favourite painter is Jackson Pollock. (It wasn't a popular answer.)

"Michael Grandage directs and, at 90 minutes straight through, he builds up the layers, not unlike the paint on a Rothko canvas, until you care deeply about both men. The connection only gets more powerful. The themes of student and teacher, father and son pulsate right along with those paintings on stage."

"The set, by Christopher Oram, is nothing short of perfect. He must have had great fun recreating those paintings and the wondrous blend of work, sweat, paint and liquor that made that studio."

Michael Billington, The Guardian

★★★★

"The delight of the piece, however, is its ability to balance theory and practice. In Christopher Oram's design, the studio really does look like a workspace, and the highlight of Grandage's production is still the moment when Rothko and Ken take a blank canvas and slap on an undercoat. The two men go at their task like demons and at one point, applying layers of paint horizontally, achieve a physical harmony that totally belies their intellectual rivalry."

"Alfred Enoch captures exactly Ken's progress from sorcerer's apprentice to articulate opponent, and wittily scores off Rothko by reminding him that, just as the abstract expressionists waged brutal war on the cubists, so they too are now being overturned. Even if I couldn't always believe that the studio would have housed such suavely phrased arguments, the play offers an invigorating 90 minutes and shows Rothko's ability to paint the town his own sombre form of red."

© Johan Persson

Natasha Tripney, The Stage

★★★

"Enoch brings a completely different energy to the production. He's a warmer presence than Redmayne was and he reframes some of the play's discussion about, say, the symbolism of blackness in art. He invigorates the play, while also making its limitations apparent."

"Grandage's production, however, goes some way to countering this. Christopher Oram's set is a kind of glorious abattoir-temple, bronzed by Neil Austin's lighting. Meanwhile, Grandage's direction provides a reminder that painting of this scale is a physical activity as well as an intellectual and aesthetic one and contains a wonderfully choreographed sequence in which the two men prep a canvas, their clothes and skin splattered in paint by the end."

Dominic Cavendish, The Telegraph

★★★★

"Molina is older, heavier, sadder – no less commanding – than he was at the Donmar in 2009; some of Rothko's thinking-aloud flows past like busy Manhattan traffic, could usefully slow a little, yet there's no discernible join between actor and character. A face from the Harry Potter films and as agile as a Wimbledon ball-boy as he darts about the replica studio, Alfred Enoch doesn't quite match the intensity of Eddie Redmayne, who scooped awards as the decreasingly submissive gofer last time, and blazed with memorable anguish."

"Yet the youth's transformation is still vividly relayed. And further niggling is beside the point. It's a joy to have this modern classic back, splendidly played, and finally reaching the wider audience it was denied – through dint of its Broadway-transferring success – last time round."

Andrzej Lukowski, Time Out

★★★★

"US playwright Logan's short, intense play has its faults, notably a rather American tendency towards excessively mannered dialogue (an early discussion of Nietzsche between the two could practically have been lifted from a episode of Frasier). And Ken has a tragic backstory that's almost impressive in its contrivance.

"But for the most part Red remains pretty special. The dialogue has its faults, but the remarkable, elemental way that the two men discuss colour is not one of them (‘one day the black with swallow the red', declares a fearful Rothko, early on)."

"The tortured artist is a naff cliche, but Molina's towering performance avoids tropes – his Rothko barely has emotions at all, seemingly wholly devoted to his work, and yet clearly his entire life is defined by an existential dread and his desire to impose order upon it."

Henry Hitchings, Evening Standard

★★★★

"There are certainly moments when John Logan's portrait of Mark Rothko feels like a sermon or a lecture. But it captures the grandeur of this famously imperious painter's vision.

Crucial to this is Alfred Molina, returning to the role he played when Logan's two-hander premiered in London in 2009. Roaring with rage and pacing like a condemned prisoner, he has both the feverish energy and the gravitas to be wholly plausible as this brilliant and titanically self-absorbed figure…Alfred Enoch brings wit and balletic physicality to a part that originally belonged to Eddie Redmayne."

"Michael Grandage's precisely choreographed production is sensitive to the play's tensions and rhythms, and there's a glorious scene in which the master and his apprentice prime a bare canvas — an exhilarating ritual that bears out Rothko's idea of art as something intimate and miraculous."