I, Malvolio at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Shakespeare’s Globe – review

Tim Crouch’s solo show runs until 9 December

Can this really be Tim Crouch’s Globe debut? As part of the season celebrating the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse’s tenth anniversary at the Globe, his long-existing solo show on Twelfth Night’s famous unfortunate arrives in curmudgeonly style. Part of his touchstone series making use of one minor (to extremely minor, in the case of I, Peaseblossom) character of a Shakespearean play for younger audiences, it’s surprising such a proficient of the Bard hasn’t graced this stage in some way before.

Twelfth Night is a vast enough play to bear the weight of the trademark Crouchian discomfort and examination of what an audience will permit. It’s a piece, after all, in which even Andrew, the fool, is afforded the line “I was adored once, too” – a hell of a scene-slowing aside, if you let it be. Crouch lets us into an affectionate understanding of what’s vital about the play, the raucous din of all that loving and laughing, as well as who pays the price for the hilarity.

Crouch’s Malvolio is an anti-theatre, anti-smoking Puritan, a denizen of outrage, the world’s order-keeper, the cleaner-upper, the sole pedant left concerned with standards and with religion. He tracks the other characters of the play by throwing his arms out – there’s Olivia, there’s Viola (“the peevish young boy-man-boy-man-boy”) and her improbable, providential brother – here’s Malvolio’s dignity, his very life, falling apart.

And he shows us how much we enjoy all that by doing the work of making us enjoy ourselves here: the well-managed chaos, his attentive characterisation, gorgeous language and elastic appraisal of who’s really in the room with him. More than any other of his plays, Crouch is at his most Stewart Lee here. Sometimes he’s more himself than Malvolio, and that’s part of the disarm machine too, though when he hurriedly repeats “I’m not mad, I’m not mad, I’m not mad,” a hush falls.

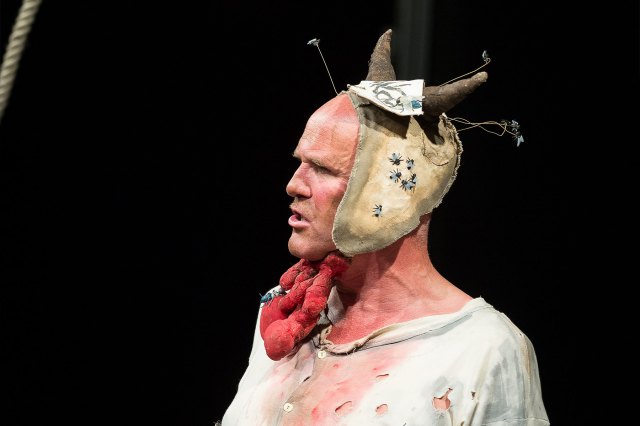

Graeme Gilmour’s design endures and sits well against the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse: still the dismaying yawn of split britches, horned hat and protrusion of red bubbles on Malvolio’s chin like a chicken comb (making for a forlorn, rejected character from Where the Wild Things Are), and the big loopy noose. It’s as if he’s been drawn by a child – though its programming and copy here at the Globe perhaps move the show a little away from its original brief for young people. Crouch of course enlists the setting itself as another thing scratching at Malvolio, more evidence of the world’s nonsense conspiring to royally piss him off. The longer we sit in this “reconstructed, Jacobean” setting, the worse it is.

Perhaps I, Malvolio sticks out a little playfully from what audiences are accustomed to from the Globe: they are beside themselves with laughter and in mischievous, contrary spirits on the night I visit. Crouch’s more than equal to it, cajoling volunteers to bully him “just for the play”. That they put up such a resistance here feels testament to how surprising Crouch’s whole affect and enterprise is to them and how up for it they discover themselves to be.

He’s such an immaculate performer and improviser that we seem to spend the smallest part of the evening speeding through the recaps of Twelfth Night, most of the time with Crouch off-script and genuinely appreciating and engaging with the audience he has, but it feels seamless.

The concept is so watertight that everything becomes grist for Malvolio’s mill. When he needs to get back on track and doesn’t feel like saying “Going to get back onto the script now, settle down,” as he sometimes does, he has such minute control over his voice that the audience quietens immediately. You might find yourself wishing that the ever-so-traditional candles in the Sam Wanamaker allowed for a better view of the glorious reddening of Crouch’s face.