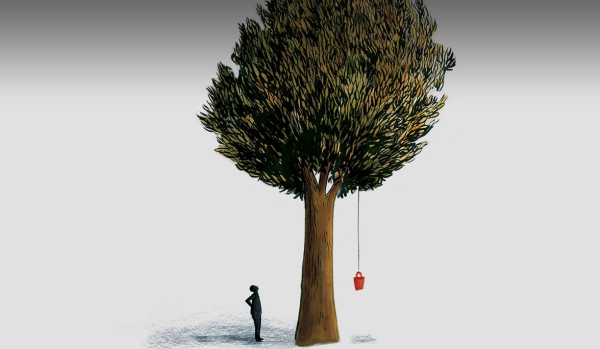

Daniel Kitson is going through a Samuel Beckett phase. Last year, in Analog.Ue, he filled the Lyttelton stage with recording devices to riff on Krapp's Last Tape. Tree, first seen the year before at Manchester's Royal Exchange, lifts its setting from Waiting for Godot: A country road. A tree. Some bloke with a coolbox.

"What you doing up a tree, mate?" shouts Tim Key, perched on said coolbox and peering up into the foliage of the large elder tree onstage. The familiar bushy beard and inch-thick specs of Daniel Kitson peer back down.

Key's character, a small-town shambles of a lawyer in a badly-cut suit and a shit tie, is here for a first date – a picnic – with a woman he met ten years earlier. Having forgotten to change his clocks, he's managed to be both late and early.

Kitson's – well – he lives up a tree. Has done for the past nine years, he claims, following a neighbourhood dispute over a local pollarding programme that's long since been resolved. What was a protest has become a way of life and, like Italo Calvino's Baron in the Trees, he's resolved not to climb down.

He's quite happy up there, mind, triple-bagging his shit and lobbing it into passing bin-trucks, watching foreign films through a neighbour's window on Thursday nights. Once a week, the tenants living in his old house deliver his groceries.

Tree is all about time. Like Vladimir and Estragon, these two men shoot the breeze to kill time; but, where Beckett sees the existential horror of hanging around, Kitson finds the good. Friendships take time to blossom. So do people: without repetition, a personal dictum is just another sentence. Actions mean more when they're repeated.

Above all, Tree is a play about commitment and the time it takes: Key's kept a candle burning for a decade based on a fleeting moment of connection; Kitson's dedicated himself to life in the leaves. Coming down would cancel its significance: he's still sticking it to the man, but doing so means sponging off his neighbours and the council. Perhaps protesting or opting out simply isn't possible.

Kitson has been more wondrous than this. He's been more intellectually dazzling. But it's entirely fitting that a meditation on time should idle away 90 minutes of your life quite happily. Tree's neither revelatory nor particularly purposive, and, come the end, you'll wonder what it was all for, but it's constantly chucklesome and gently ponderous throughout.

That's what Kitson and Key can do: patter away for hours, entertainingly and interestingly enough. Their small-talk is second to none, from the merits of megaphones to the pleasures of a good dappled light, and even if Tree can feel like stand-up twisted into theatre, that's a big part of its charm. It's a play that gradually slows us down and just as Key starts irritated by Kitson's circuitousness then settles, Tree coaxes us to simply sit back and enjoy. Time isn't a commodity, after all. It's meant to be wasted.

Tree runs until 31 January at the Old Vic Theatre