The Gap at Hope Mill Theatre, Manchester – review

Cartwright’s new two-hander opens at the much-loved Manchester venue

You don’t even need to see the play to know that the title is going to be a stonking metaphor. But if you think it seems obvious and so on-the-nose that it could make it bleed, you need to see the play.

Writer Jim Cartwright made his name as one of the great social chroniclers of the north with Road, unpicking Lancashire life in one decade. In this new play – his first for seven years – he sweeps across several. Not that he’s interested in social commentary here. This is a shallow comedy about two friends who daringly move to London in their youth, where their relationship frays and they spend the subsequent decades subsisting in its absence.

The whole production is delivered in this unsubtle register. Andrzej Goulding’s set uses panels that forever drift apart and open up a gap. As if we couldn’t infer the emotional and physical distance between them, one of the pair endlessly calls it out as explicitly as “there it was: the gap”, while they cast their arms apart to underline it further still. There are blunt song cues, too, such as Elvis Costello’s “She” as he reminisces.

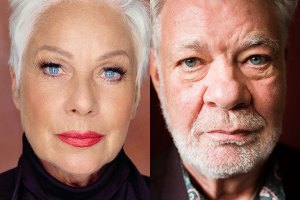

There’s never anything behind it, nothing gradually surfaces to blindside us or the characters, because it’s all foregrounded. They frequently wonder aloud how the other is doing and vocalise the transition from conviction to regret. Matthew Kelly and Denise Welch also come out of the starting blocks at maximum intensity, then maintain that level, like stand-ups, without building and developing. Walter is immediately arch, with a tiringly unabating stream of one-liners.

This style might work as a radio play, but feels heavy-handed as a piece of theatre. Cartwright’s characters don’t so much call back memories as bombard them at us. Its series of short scenes offers thin snapshots like the collage of magazine cuttings occasionally projected. Anthony Banks directs a constant whirlwind pace through them all, so they flood out and never linger.

The tone is exacerbated by Cartwright’s crass script. Corral takes up sex work to make a living, but its idea of interrogating the complicated effects on a young woman – and of her soulmate assisting – is titillating details: “the four-inch gap between the stocking top and knicker ridge”. It’s only ever a comic subject, as she adapts through the years to porn, adult-calling and finally, selling used underwear.

Kelly manages to give Walter some depth. His facial dexterity scrunches into withering looks or crumples into deflation. The way his features always seem to sag and droop seems as much with dejection as age. When he cries, it’s not just his lips that quiver but his whole face that trembles.

Welch’s delivery is slightly vacant and disconnected. It works to suggest naive delusionality, but not pain and vulnerability. She spends the second half effectively imitating Shirley Valentine, opening with her on a sunbed in Malta. It’s hard to agree when she tells us towards the end: “But you know me”.

The actors are lumbered with an unnecessary welter of tertiary characters who they simply send up with ridiculous costumes. After treating the central pair so fatuously, the play reaches at the end for unearned pathos where it expects us to suddenly care. The distance between this and a rich, layered, rounded play isn’t a gap, but a gulf.