Review: Khovanshchina (Wales Millennium Centre, Cardiff)

Mussorgsky’s great historical opera in an ambitious revival by WNO

© Clive Barda

There were no stars on the stage of the Millennium Centre, at least not in the accepted sense of the term, and you’ll only find four at the top of this review. Yet that elusive fifth shiner has been knocking hard at my chamber door, begging for admission. And it has a case.

Khovanshchina: the title alone is a deterrent, but don’t let that put you off. Mussorgsky’s last opera, unfinished at bis death and completed (then later re-completed) by such figures as Rimsky-Korsakov, Stravinsky and Shostakovich, is a bewildering, thrilling and musically overwhelming evening of total theatre.

It’s a political story of old Russia that deals with tensions between Boyars (powerful barons), aristocrats (especially the honorary princes) and the Streltsy, a brutal private army. Caught between these factions are the Old Believers, a religious sect of free thinkers, and the opera focuses on one of their number in particular, the fortune teller Marfa. She alone, it seems, embodies all that is good and courageous.

David Pountney‘s production for Welsh National Opera, first seen in 2007 in an English translation (now jettisoned in favour of the original Russian), offers spectacle on a grand scale within excitingly chaotic designs by the late Johan Engels, Pountney’s lamented colleague who also breathed life into Lulu and Pelléas et Mélisande. The set is an abstract cousin to John Napier’s for Cats, a ramshackle world that can shift time and place in a twinkling. Pountney uses it imaginatively and ensures it holds the interest across a long evening.

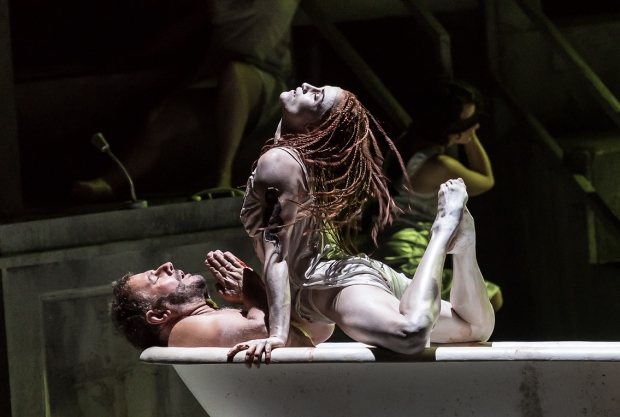

The music is generous and lush, with the kind of choral writing any choir would kill for, let alone a crack ensemble like the WNO Chorus. Add a strong cast of solo singers, many of who only appear for a few minutes, and it’s sensory immersion. Indeed, Prince Ivan, the baleful boss of the Streltsy, meets his end in a bathtub after a startlingly erotic close encounter with his Persian Slave – danced by Elena Thomas to Beate Vollack‘s unrestrained choreography – and if that episode conjures thoughts of the Marat-Sade, it also gives a clue to the style of the evening as a whole.

'Musically ecstatic'

Robert Hayward summons up all his bass-baritone resources to invest Ivan with dark authority, and his every appearance sparks chills. Mark Le Brocq complements him as the cynical Prince Golitsyn, while by way of contrast the young Prince Andrei is given a wellspring of sympathy by tenor Adrian Dwyer as he cleaves to the light and shares his doom with Sara Fulgoni‘s Marfa.

It took a while to acclimatise to Fulgoni’s clouded timbre and her incipient vocal beat, but so committed was her performance that she won me round. There were no such doubts where Adrian Thompson (the Scribe) was concerned, nor indeed Miklós Sebestyén as Dosifei or Simon Bailey as Shaklovity, all of whom sang and acted with powerful directness.

WNO’s music director Tomáš Hanus revelled in the opportunities this colourful score afforded him for mood and emphasis, and his orchestra responded with virtuosic assurance.

In the end it’s the opera’s choppy structure that’s shot the fifth star out of the running. Whole chunks of Khovanshchina are musically ecstatic, but dramatically the work’s strengths come and go. Pountney, with one reservation, has done the best anyone could do with an piece that jerks along from A to B; the niggle is that if you don’t already know the opera you might struggle to puzzle out what happens at the end. The Old Believers are supposed to self-immolate, but instead of flames the whole thing stalls on an episode of mawkish religiosity.

There are further performances of Khovanshchina in Cardiff (7 October), Llandudno (24 October) and Birmingham (31 October).