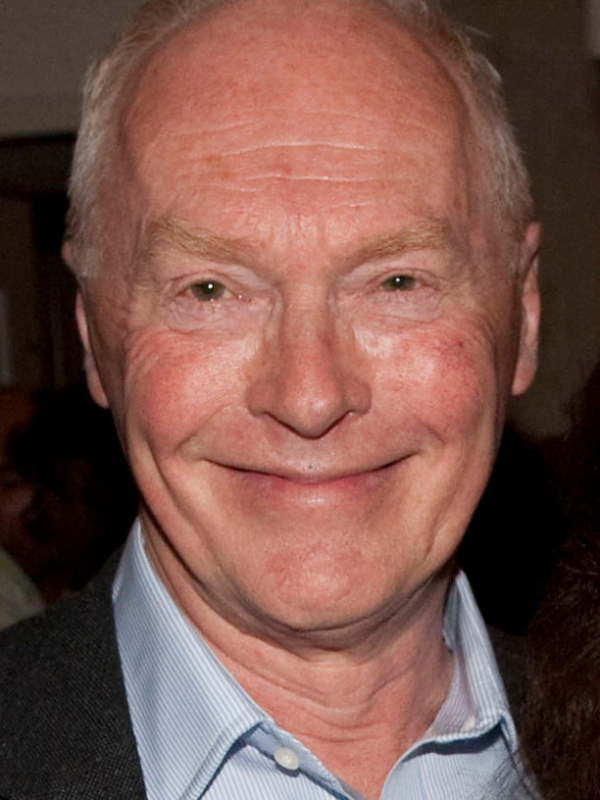

Nicholas Wright: 'Eugene de Kock is like Myra Hindley in South Africa'

As his new play ”A Human Being Died That Night” opens at Hampstead Theatre, Nicholas Wright talks to Michael Coveney about returning to his South African roots

© Jesse Kate Kramer

"As long as your crimes were politically motivated, you got off," says Nicholas Wright, the brilliant and self-effacing Peter Pan of the British theatre establishment, of his new subject, Eugene de Kock, the notorious assassin of the South African apartheid regime.

Unfortunately for him, de Kock was exposed by an enterprising journalist in the Transvaal and is currently serving two life sentences and 212 years in prison. Everyone else, apparently, is running around in restaurants, shops and car-phone businesses.

Wright's latest play, A Human Being Died That Night, opening at Hampstead Theatre's downstairs studio this week (press night is 28 May), is based on a book of interviews the psychologist Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela conducted with de Kock in 1997; how did a fundamentally moral person become a mass murderer?

Wright's credentials are unimpeachable for this duologue, first tried out a couple of years ago in Hampstead (without reviews) and recently acclaimed at the Fugard Theatre in Cape Town; he's from Cape Town himself, coming to LAMDA to train as an actor before opening the Theatre Upstairs at the Royal Court in the early 1970s and acting as both literary manager and playwright at the National for many years.

He is, he says, always interested in morality and relationships, and most identifies, among his own plays, with the cultural dynamics in Cressida, his wonderful play about boy actors in the post-Shakespearean theatre (Michael Gambon starred in the 2000 West End premiere) and with The Reporter (2007), a National Theatre play about the BBC journalist James Mossman who was gay, mysterious and a member of MI6: "You never leave MI6; when Mossman died, they came and cleared out his house immediately."

But it's not so much politics, or the politics of surveillance, that gets him going, it's corruption and how it affects people. "South Africa is terribly corrupt, though the Western Cape, where I come from, is much better. Nothing has happened there to change anything in the play – although there is a possibility that de Kock will be released at some time – and it's based entirely on what Pumla says, and is highly critical of the ANC, the ruling party."

De Kock (played by Matthew Marsh) blew up offices and people, ran death squads, committed gross acts of torture, kidnapping, fraud and assault and yet he opens up to Pulma (Noma Dumezweni), a black woman professor who served on the Truth and Reconciliation Committee that has created a forgiveness loophole for de Kock and his crew.

"We don't know about him here," admits Wright, "but he's like Myra Hindley over there, absolutely famous and guilty as hell. I saw Pumla's book in the Charing Cross Road, read it, and thought what a fantastic play it might make. I feel quite evangelical about it."

Does the actor have to like this monster? "Of course. He's a very witty, crafty and ironic person. I've made up stuff, and used trial transcripts. Nothing happens in the play except – and it's a big 'except' – Pumla changes as a black woman after meeting him, and he changes in that he repents."

© Dan Wooller

It's almost incredible that Wright is half way through his eighth decade; until, that is, you consider his credits. He's had as many plays produced at the NT as Alan Bennett, including his riveting study in psychoanalysis, Mrs Klein (1988), still performed all over the world; his beautiful Olivier award-winning play about van Gogh, Vincent in Brixton (2003); the monster adaptation of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials (2003); and his intriguing story of the early days of cinematography, Travelling Light (2012).

Then there are plays at the RSC and Riverside Studios, adaptations of Ibsen, Chekhov, Marivaux and Pirandello (Juliette Binoche was in Naked for him at the Almeida) – all done from literal translations – as well his associate directorship at the NT, his handsome volume of the history of British theatre with Richard Eyre, Changing Stages, his own indispensable 99 Plays, snapshots of world theatre, and his terms serving on the boards of both the Royal Court (where he was joint artistic director in the late 1970s) and the NT.

Phew, time to take a break, surely? Not really. The autumn sees another new play, Regeneration, adapted from Pat Barker's best-selling First World War novel, and opening in late August at the Royal and Derngate, Northampton, before going on tour. Does he not regret turning down Nic Roeg's offer to train as a cinematographer after working as a runner on John Schlesinger's movie Far From the Madding Crowd?

"When I told Nic that I was going to work in the theatre, he said it was a silly little parish. But I'd met Bill Gaskill and Peter Gill through my friendship with Harriet Devine [daughter of George Devine, founding artistic director of the English Stage Company at the Court] and knew I had a flair for theatre. I understand theatre, I just do, though I was a rotten actor and a not very good director, it didn't suit me."

He says the Court suffers today from a general de-politicisation in the theatre, and in the critics for that matter. "But it's still the best place to put on a play," he says, "as everyone in the building is concentrating on the show in hand, which is not exactly what happens at the National."

So does he think of himself as the eminence grise of British theatre, this puckish, quizzical, interesting man who shares his life with David Lan, artistic director of the Young Vic? "Not at all. I've been very lucky to work with such clever people, Bill Gaskill and Max Stafford-Clark, obviously, at the Court. Peter Hall was kind of brilliant, like Bill Clinton; watching his mind work was astonishing. And of course Richard Eyre and Nick Hytner are so clever. I was a child actor, with no intellectual background at all!"

He left home aged 18, paid for by his parents to train at LAMDA – his father was a commercial traveller who joined the army when Nicholas was six months old, "and I never saw him till I was five" – so A Human Being Died That Night may represent some sort of homecoming? "Not really, I feel completely at home in Britain." But your background never leaves you, even if you are so thoroughly conditioned by your work and colleagues, as Wright has been over the intervening, highly productive and influential years.

A Human Being Died That Night continues at Hampstead Theatre until 21 June