Guest blog: The lasting legacy of the alternative theatre movement

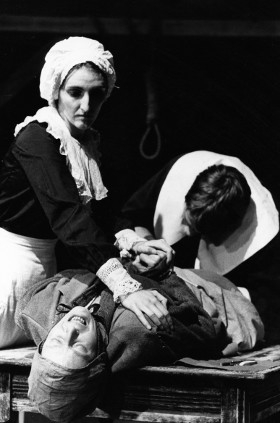

Susan Croft, curator of ”Re-Staging Revolutions”, a new exhibition from Unfinished Histories celebrating the work of alternative theatre companies and venues in Lambeth and Camden opening this Sunday at Ovalhouse, talks about the legacy of the alternative theatre movement

The alternative theatre movement had its heyday from the late 1960s to the 1980s, a period that started with the protest movements against the Vietnam war, the optimism of the counter-culture, Black Power, Women’s Liberation Movement, the Gay Liberation Front, went through the political struggles of the 70s, focused on unions, equal pay and revolution, all of which had their counterparts in theatre, to the advent of Thatcherism, Ken Livingstone’s GLC, Arts Council cuts, the growth of computer technology, all of which had major impact on it.

Theatre played a part in these movements for social and political change: the visibility of gays on stage in companies like Gay Sweatshop or the Brixton Faeries was intimately connected to the highly theatrical Gay Pride marches and the refusal to be closeted. The opening ceremony of the Paralympic Games last year with Graeae singing Spasticus Autisticus at its heart and their director Jenny Sealey at its helm, enacted a similar refusal of invisibility and demand for access in every sense to spaces, to power to the tools of creativity.

All of the opening and closing ceremonies, with their satanic mills exploding from the ground and other grand visions, would have been unthinkable without the work of such pioneering alternative theatre companies like Welfare State International, Action Space, and IOU, that started out of the hugely creative 60s art school scene, whose experiments massively expanded theatre vocabularies with their large-scale fire ceremonies, enormous puppets, giant inflatables, and processions.

Their work and that of community arts innovators like Inter-Action energised and organised whole communities as participants. At the heart of the movement was the idea to make theatre accessible through ticket prices, through touring, through taking theatre out of traditional buildings into venues that were strange and surprising and new, from disused swimming pools to warehouses, tube trains, zoos, shopping centres, the foundation of promenade and site-specific theatre today.

The movement also created its own network of local arts centres across the country as well as going into schools, prisons, one o’clock clubs and day centres, taking theatre to those who would otherwise not have access to it. The legacy of venues remain with us from BAC to the Tricycle, the Bush to Ovalhouse (celebrating their 50th anniversary this year).

Locally much has been eroded through cuts or impacted through increased legislation and restrictive curriculum demands in schools, though the area of ‘applied theatre’ continues to grow with companies like Cardboard Citizens or Clean Break among the inheritors (the early work of Clean Break was supported by Stirabout, the first company to work in prisons). The movement developed the flexible black box space and many innovators in design started there including Bill Mitchell of Kneehigh who worked with Theatre Centre and major lighting designer Rick Fisher, who made his first work at Ovalhouse, then as now a burgeoning centre for theatre experiment.

So many individuals developed their craft through their work in alternative theatre companies which were above all places of questioning and experiment: writers like Howard Brenton, David Hare and the late Snoo Wilson (Portable Theatre), David Edgar (The General Will), Bryony Lavery (Les Oeufs Malades), Caryl Churchill (Joint Stock), Tash Fairbanks (co-author of the acclaimed currently touring Fog, who started with Siren Theatre) and many more.

Directors in theatre like Simon McBurney (Complicite was part of the movement), Annabel Arden (1982 Company), Deborah Warner (Kick), Stephen Daldry (Metro Theatre) or film and TV: Mike Figgis (The People Show), Steve Shill (Impact Theatre Co-op), the late Antonia Bird. Hugely influential arts managers grew up through the movement from Ruth Mackenzie (Moving Parts) to Jude Kelly (Solent People’s Theatre) to the late Jenny Harris, co-founder of the Brighton Combination who then set up the Albany Empire before leading the National’s Education department.

That these highly influential women came through the movement is no coincidence. Much of the work was centrally informed by feminism: there were at least 80 women’s theatre companies actively involved in the movement. Black and Asian theatre was also central: Mustapha Matura’s first play was commissioned for the Black and White Power Plays season at the lunchtime Ambiance venue, run by ED Berman’s Inter-Action. Matura later co-founded Black Theatre Co-op which with Temba, Umoja, Theatre Of Black Women, commissioned numerous black writers and developed the careers of numerous actors and directors.

The movement through their visibility and initiatives like the influential Black Theatre Forum also implicitly or explicitly challenged mainstream institutions over their casting, commissioning and audiences, helping build the legacy which was celebrated earlier this year with Walk in the Light at the National Theatre.

To read more about the exhibition, visit Ovalhouse's website