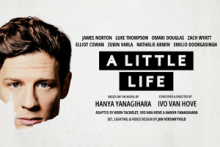

Did critics show a little love for ”A Little Life”?

Sarah Crompton, WhatsOnStage

★★★★

“On stage, where there is less room for the characters to expand, it is even more intense. What holds the attention, is the sheer intensity of the performances. As Jude, described as “a magician whose sole trick is concealment”, James Norton is not only committed but also subtle. Because of the structure of the piece, he has to move between sophisticated, outwardly composed New Yorker and frightened, snivelling child in the blink of an eye. He has to play agonised and concealed.

“He has to sing Mahler and be consumed by guilt. He does all this with absolute conviction. As the action progresses, his clothes stay bloody, as if the contents of his soul have finally been exposed, and Norton allows Jude to thaw just a little, constantly suggesting the agony beneath the gentle sheen.”

Nick Curtis, Evening Standard

★★★★

“Van Hove, who adapted the text with the author and Koen Tachelet is horribly faithful to the story, but also mines a seam of hope I didn’t find in its 814 pages. Zubin Varla is achingly open, almost skinless, as Jude’s adoptive father, Harold.

“Luke Thompson’s breezy charm as Jude’s friend and lover Willem makes his later rage and sorrow more poignant. Omari Douglas gets a few deliciously acid, scene-stealing appearances as painter JB, while Zach Wyatt is stuck on the sidelines as architect Malcolm.”

© Jan Versweyveld

Sam Marlowe, The Stage

★★★★

“Jan Versweyveld’s red-floored set features a working kitchen at one end, work studios for JB and Malcolm at the other, and sofas and a washbasin in between. Its homeliness is undercut by the presence of household instruments of violence everywhere, from the flames and knives used for cooking to the stash of razor blades, surgical gauze and box cutters that Jude keeps secreted in the bathroom.

“The sequences of self-harm are excruciating to watch, the New York street scenes on the video screens that flank the stage pixellating, just as vision does before unconsciousness. A live string quartet supplies a soundtrack that skitters and keens, and Norton’s bleeding body is more than once lifted and carried, Christ-like, by an abuser or by his friends, all of them in some sense either father or brother. Family, and faith, might offer salvation; or equally, just more betrayal and despair.”

Dominic Cavendish, The Telegraph

★★★★

“Norton is superb at suggesting hidden depths, that impassivity acquired in the exploitative company of a Catholic monk who first befriended then betrayed him, forcing him into child prostitution. The book has been accused of piling on the agony but it doesn’t feel gratuitous here.

“The most perturbing scenes involve Norton baring his scarred back, achingly vulnerable as he strips off in the first half to be spat on and shoved in revulsion by a sadistic lover. In the second, unforgettably, he’s forced to run madly for his life by another false saviour turned tormenter (Elliot Cowan is all three men, accentuating the continuum of abuse): Norton’s face becomes a silent scream of wretchedness.”

Fiona Mountford, The i

★★★★

“This is without doubt the most gruelling piece of theatre I can recall seeing; incredulous disbelief at the ordeals one man goes through mounts until we feel we can take no more. How much pain can one little life bear?

“Yet in the interstices of horror and abuse, there are transcendental moments of love and affection, beautifully played by the eight-strong cast. How Norton manages this performance once a day is astonishing, but to do it twice on matinée days is a feat of endurance that deserves some sort of medal for bravery.”

Sarah Hemming, Financial Times

★★★

“There’s great expressionist use of the set and music: background videos of New York distort as Jude reaches breaking point and the live music (designed by Eric Sleichim) scrapes and scratches.

“And yet. There’s something here that is deeply unsettling. There are major problems translating the novel to stage that Van Hove has not been able to surmount, and issues within it are amplified. Without the slow evolution of the 700-page narrative, the story becomes a relentless pile-up of pain and physical suffering.”

Andrzej Lukowski, Time Out

★★★

“To his credit, Van Hove never makes it feel pulpy or trashily exploitative, more of a meditative treatise on how life is unutterably cruel and shit. But in doing so it becomes a sort of experiment in terror, an attempt to see how an audience will react to seeing unimaginable horrors piled upon a single character with almost nothing in the way of relief. There’s some seating at the back of the stage and I wonder if its main purpose is so we can see the shocked faces of our fellow audience members’ faces.”

Arifa Akbar, The Guardian

★★★

“There is something heroic in the staging of this story in the West End: resolutely bleak with no catharsis and cyclical violence, it is an almost anthropological study of pain. It is staged with utmost intelligence too: moments of pitched emotion are accompanied by the nerve-jangling sounds of violins and cello; a rolling film-scape of New York’s streets on either side of Jan Versweyveld’s set brings an implacable forward movement as we march through Jude’s life and its inescapable suffering.

“But for all its sophistication and searing qualities, it is a discomforting production. The gripe, for me, lies with Yanagihara’s original story, the shortcomings of which become all the more jarring on stage.”

Alice Saville, The Independent

★★

“Much will be made of Norton’s bravery in spending so much of this play naked, cutting himself, or being part of harrowing scenes of child abuse. And yes, it’s impressive. But somehow Norton doesn’t convey Jude’s inner life, or do enough to make you desperately root for him.

“That’s partly the fault of Van Hove’s cold, surgical, humourless adaptation, but it’s more so the fault of Yanagihara’s book itself. There’s a child-like naivety to Yanagihara’s sense of how the world works. Here, it’s perfectly possible to be dealing with life-altering physical and mental disabilities while simultaneously having an unimpeded career as a top New York corporate lawyer, and also volunteering at a soup kitchen at weekends.”

Clive Davis, The Times

★★

“The play, inevitably, can only deliver a precis of a book that sprawls over some 700 pages. Sometimes the pace reminded me of the unhappy stage adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s Tudor epic The Mirror and the Light. The other obvious problem is that the storyline — including the bleak twist at the end — is so implausible. Strip away the gore and the gossip about Norton’s private parts, and what do you have? A stylishly mounted, second-rate melodrama.”