Review: Jerusalem (Watermill)

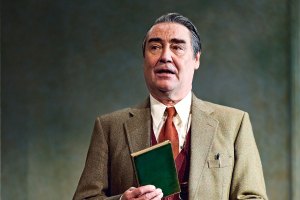

The Watermill theatre in Newbury revives Jez Butterworth’s superb play with Jasper Britton in the lead role of Rooster Byron

© Philip Tull

I've said it here before: Jez Butterworth's Jerusalem, first seen at the Royal Court in 2009, is a contender for the best play of the 21st century. But we haven't been able to test that proposition because after that blistering first production, centred around a performance of genius from Mark Rylance, we haven't seen it again.

So it is a brilliant stroke for the tiny Watermill Theatre to revive it. And it is even more thrilling that Lisa Blair's new production, led by Jasper Britton as Johnny 'Rooster' Byron, modern lord of misrule, is just as devastating, pertinent and incandescently funny as you could hope. Its themes of a lost England, of poverty and disaffection, of ancient woodlands under threat from the need for new homes, of individualism versus the need to conform, fit perfectly into this place, where the setting is idyllic but the nearby high street is scarred by empty shops.

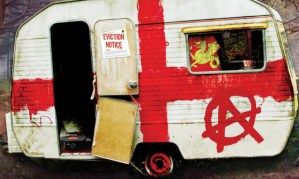

In the years since its premiere, the play's themes have become ever more relevant. And you can see exactly why it has become an A-level text. Set on St George's Day, as a small town in Wiltshire get ready to celebrate an ancient fair with modern rites, its strength lies in the way that it combines metaphorical heft with naturalistic vigour. The young kids gathering like a magnet round Rooster's battered caravan, lured by drugs, booze and the warmth of their shared conversations, are entirely believable.

So is Rooster himself, at war with Avon and Kennett council, who want to evict him to build new homes. He is both the man you'd avoid if you met him down the pub, drunk and disgusting, but also the one you'd irresistibly want to talk to, as he weaves his tall tales of being kidnapped by traffic wardens or being born with a bullet in his teeth. The combination of the everyday and the fantastical is built in the structures of Butterworth's dense and deftly timed sentences: "I once met a giant." Pause. "Just off the A14". But the mythic content of those stories, the sense that Byron belongs to an older, more powerful world than the alienating one of today, underpins the entire play. Its resonating questions about the nature of society and national identity are huge: "What is an English forest for?"

Britton's terrific Byron is more desperate and less mercurial than Rylance. He gives the sense, in his slow movements, of almost being rooted to the earth. "I am heavy stone, me. You pick me up, you break my spine." When he pulls himself up to his considerable full height and claims possession of Rooster's wood, you see a proud man who is not to be meddled with. But the melancholy lurks behind his eyes. So too does a sense of danger, of ingrained outsiderness – "I am no-one's friend" – though this is finely balanced with what feels like real concern for the youngsters who nestle around him, and their right to grow up in freedom.

Blair's direction impresses for the subtleties she has found in those relationships. With a setting by Frankie Bradshaw that faithfully recreates the clutter around the caravan and winds May ribbons around the pillars of the theatre itself, she brings an element of tenderness into Byron's relationships with those around him. This is particularly true in the quiet scene with Dawn, mother of his son Markey, sensitively played by Natalie Walter: she looks at Byron with love and compassion as well as with despair. It's a beautifully judged reaction that catches the balance of the play.

The entire cast (doubling a few parts) find the same humane clarity. Each character is carefully delineated, not falling into caricature, from Robert Fitch's Wesley, dressed in embarrassing morris dancing gear and mourning the May queens past, to Richard Evans' professor burbling about the meaning of May Day, and Nenda Neurer's Phaedra, lost in the woods, fleeing an abusive stepfather, singing Blake's anthem of old England. Sam Swann is quietly wistful as Lee, escaping to Australia but worried about what he will leave behind, and Santino Smith brings total belief to his part as Davey, the abattoir worker so tied to his home town that "If I leave Wiltshire my ears pop." As Ginger, the ultimate misfit, Peter Caulfield has a permanent whiff of dissatisfaction; his drugged-up confusion is a wonderful comic highlight.

It's just all so rich, so full of energy and passion. Three hours simply fly by. This vision of England, at once fantastical and real, funny and tragic, wild and profound is a modern classic. It rewards repeated viewing and will – we now absolutely know – retain its towering status in repeated interpretations. Congratulations to the Watermill for beginning the process.