Terence Rattigan’s Summer 1954 on tour – review

James Dacre’s double bill includes Table Number Seven and The Browning Version

The renaissance of Terence Rattigan is one of the more surprising elements of British theatre in the 21st century. Dismissed by the establishment following the rise of the ‘angry young men’ brigade of Osborne, Wesker, and their ilk, his works of repressed emotion and stiff-upper-lip morals vanished from our stages. Yet over the past fifteen years, here he has come, supported by institutions like the Theatre Royal Bath; that have almost made him an in-house dramatist; to become a key component in our modern-day scene.

At his best, for example in the National’s After the Dance or more recently here in Tamsin Greig’s The Deep Blue Sea, Rattigan’s plays burst through the constraints of hidden emotion, tearing at your heart. However, when seen in slightly creaky, old-fashioned vehicles such as Summer 1954, a pairing of two of Rattigan’s one-acters, the texts feel fusty and artificial, though well-constructed, containing little human emotion.

This is a shame as Table Number Seven and The Browning Version are pieces, evaluated again in 2024, that feel brave and bold, small revolutions in well-made plays. In the former, the guests of a private hotel must decide whether to cast out one of its own when it is revealed he has made importune passes at several men in the park, while the latter sees a long-serving classics teacher re-examine his choices when a student gifts him a copy of Robert Browning’s translation of Agamemnon.

Both plays examine the forbidden. In James Dacre’s production of Table Number Seven, he has used the text discovered years later that changed the Major’s charges from sexual harassment of women in a cinema to soliciting men in the park, while the classics master deals with knowing his wife is flaunting an affair right in front of his nose. Paced perfectly by Rattigan, they are excellent examples in how to construct a play. Dacre’s production, however, is an example of how not to play them.

Compiling a compelling cast together, he has directed them in a way that can only be described as actorly. Too often, rather than playing between the lines, the actors direct them out front, landing certain resonances too hard, letting their rich voices do the lifting. There is stiffness abound. It occasionally feels like we’re back in the 50s watching them.

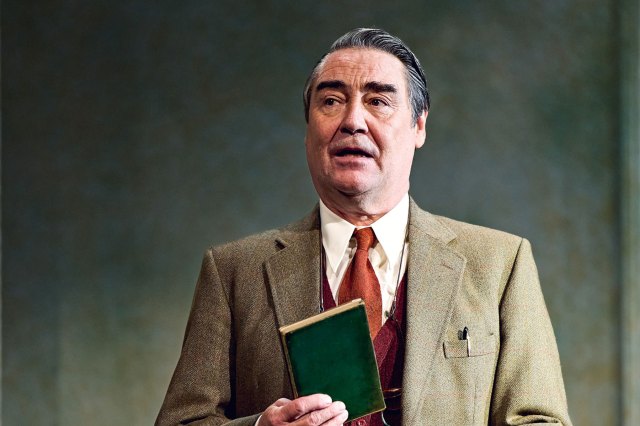

Nathaniel Parker as both the general and the classics master rises above this, his two performances grounded in something richer. His general rubs his eyes wearily as he realises that his long-held secrets are out in the open, while his teacher carries the weight of the world on his shoulders when he discovers his pupils fear him. Portraying two crumbling men with barely a hint of expressed emotion, Parker finds a truth while others around him portray a role. It is also a great opportunity to see Siân Phillips at the age of 91, still enrapturing a stage, her voice deep and resonant, her Mrs Railton-Bell a crusading gorgon who eventually finds her power overseeded.

These are two reasons to go see this, but in many ways, this production, with its old-fashioned mentality and stiff theatricality reveals why it was so easy for Rattigan to be forced off our stages for so long. He deserves better.