© Jane Hobson

Imagine a production that takes the basic premise of Romeo and Juliet but transports it to a mythical time, where two tribes fight over control of a magical forest and the elements. Pass it through a writer's room that applies just about every musical theatre cliché in the book, along with the need to mention the word fire every five seconds, and you will have a decent idea of what Vanara is about.

Despite already having a solid base from which to write a musical (West Side Story parallels are unavoidable), this production takes an eternity to get going. Half an hour into the story all that has been established is that there are the two tribes, one with fire and one without, but that's about it: things don't speed up a great deal from there.

Nowhere near enough happens in Vanara to justify how long it is. The start of the second act is a perfect example of the tightening that should have been obvious: three unmemorable numbers from different characters follow one after another about the same topics, whilst the plot stays stationary. When the production's end arrives, it does so in a messy and confusing manner: differences are laid aside in an instant with a piece of information that seems pulled out of thin air – leaving you wondering what the point in the previous two and a half hours was.

You'll also be left questioning why the set isn't a little more populated throughout. Vanara's best scenes always involve more than two or three characters on stage at the same time, allowing for Eleesha Drennan's choreography to shine through – as it does in the memorable dream sequence or a fight scene towards the end. The latter actually feels quite exciting given the ponderous nature of what has preceded it, but too often this production leans towards one or two characters on stage and the set feels cavernous and wasted in these moments.

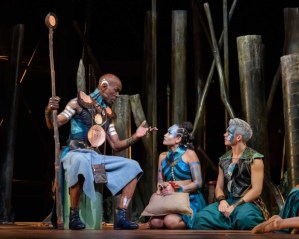

There are some redeeming individual performances from the cast, particularly stand-outs Kayleigh McKnight as Sindah and Emily Bautista as Ayla, but, honestly, they are left with far too much to do here. The Oroznah (played by Johnnie Fiori) is perhaps the only character with dialogue capable of inducing sustained audience laughter, but even this feels like it owes more to channeling The Lion King's Rafiki rather than any inspired script-writing.

The dialogue is generally incapable and unwilling to move beyond the same few tiresome phrases about courage, loyalty and, of course, fire. Never forget about the fire.