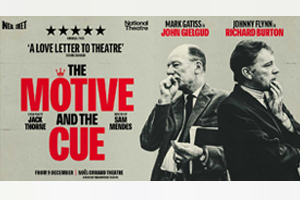

The Motive and the Cue West End review – the National’s hit play holds added significance at the Noël Coward Theatre

Sam Mendes’ acclaimed production runs until 23 March

There is something quite magical about sitting in the Noël Coward Theatre, where John Gielgud played Hamlet in 1934 for 155 performances and seeing Mark Gatiss play John Gielgud directing Richard Burton in Hamlet in 1964.

It’s not just that the transfer of the National Theatre’s magnificent The Motive and the Cue to this particular West End theatre means that the audience and the cast are part of their own piece of theatrical history. It’s more that the play itself opens up just those vistas of life and art, celebrating and exploring the way that theatre is like a box of mirrors, revealing and illuminating past and present, the personal and the public.

That’s why people who don’t give a hoot about Shakespeare – “Uncle Will” as Gielgud calls him – or the fact that Burton’s Hamlet on Broadway was the longest-running ever, or the knowledge that a great production sprang from an unhappy rehearsal process where the two men clashed, still find so much to cherish and admire in Jack Thorne’s play. It is about theatre and about Hamlet, but it is also about age and youth, fame and obscurity, and all the doubts and fears everyone is prey to.

Seeing it for a second time, it has got richer and deeper as the cast – most of them transferring with the play – have burrowed into their parts. It has an inbuilt watchfulness. Because most of the action is set in a rehearsal room, wonderfully created by Es Devlin as a bare space with long windows and lit by Jon Clark to mark the passing of the hours, the audience watches actors gathered around a central arena, watching other actors.

Director Sam Mendes builds these tableaux with an artist’s eye. They are matched by the careful groupings in Burton’s hotel room, where his new wife Elizabeth Taylor holds raucous court like a medieval monarch. Again, we watch them watching her. As Taylor, Tuppence Middleton brings enormous vitality to these scenes, suggesting the wisdom borne of long experience that made her such a fascinating figure as well as her “tremendous bosom” as Gielgud calls it.

These general scenes are beautifully animated, with Luke Norris’s anxious William Redfield particularly fine, but the play pivots around three epic encounters. Two are between Gielgud and Burton: one furious, where a drunken, raging Burton humiliates his director in front of the rest of the cast; the other revelatory, where Gielgud unlocks something of Burton’s unhappiness and leads him to discover “his” Hamlet, his route through the play. In between, there is a gloriously witty scene between Gielgud and Taylor, where she acts as peacemaker.

These are all deeply human moments, and there is great humanity in Thorne’s writing. You’d expect the play to be Burton’s show. Yet for all Flynn’s intelligent energy, The Motive and the Cue is grounded in Gielgud and in Gatiss’s portrayal of him, which has only gotten better with time.

He manages to combine a veneer of impersonation – the voice with its dying falls, the tilt of the head, the arms folded across his body in conscious protection – with an absolute conviction of emotion. His timing, both humorous and tender, is perfect. It would be hard to find anyone who can put more meaning into the word “vulgar”. But more importantly, Gatiss seems to embody Gielgud in his soul; even when he is not speaking he holds absolute focus on what is going through the man’s mind.

In the rehearsals, he gives a little moue of pleasure when he announces he is playing the Ghost “if the company will have me”; when he is watching Burton give a line reading he does not like, tension and unhappiness race across his pained face; in a hotel room with a boy he brings up from the street because “I just wanted to do something reckless”, he crumbles with sadness and suppressed grief, which he attempts to push away. “I was born with my bladder too close to my eyes.”

This Gielgud is – like the real man – often very funny. But it is the triumph of both play and performance that he is so much more than that. He becomes a symbol of human frailty and of resilience. In his belief in art, he becomes a beacon for life.