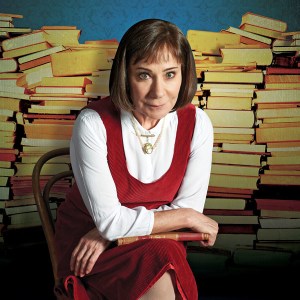

Stevie (Hampstead Theatre)

Zoë Wanamaker stars in this revival of Hugh Whitemore’s award-winning play

Zoë Wanamaker's voice is the making of Stevie. It is an orchestra of a voice, and sometimes the wind section leads, sometimes the brass. She can scurry up to her upper register, like a runaway violin, and drop down to the low notes like timpani. So when she recites Stevie Smith's poems – melancholic and mischievous as they are – there's a simple pleasure in just hearing her speak.

Hugh Whitemore's play, first seen in 1977 with Glenda Jackson in the lead, is a bio-play spun from the subject's own words: her poems, letters and chatter. Smith lived, all her life, in a suburban house in Palmers Green; for a long time with her "Lion Aunt" (Lynda Baron), then, in later life, alone. She contracted tuberculosis as a child, and somehow came to be defined by it: exhausted by life and preoccupied by death, which saunters through her poetry like an old friend with its own set of keys.

Wanamaker diagnoses a case of arrested development. Dressed like a young girl in her Sunday best – white tights, buckled shoes, red corduroy dress – she shuffles round the house, too tired to lift her feet, or sits on a poof with her toes pointed in. She clings to her childhood nickname, Stevie, after a jockey, Steve Donaghue. This is a woman who retreats from life, tucking herself away in the suburbs, content just to write around menial secretarial work, rather than impose her talent on the world. Men come and go – all played by Chris Larkin – but her relationships stop short of sexuality. "I don't feel up to being a good wife," she explains.

Not that she's dour or depressed; Smith has the outsider's ability to see life, the world, and its people as they really are, and Wanamaker's impish side suits that beautifully. She slices, machete-like, through middle-class pretensions and sees the inherent absurdities of life's anguish. Not that she's immune to it: her suicide attempt comes out of the blue. "Not waving," as she famously wrote, "but drowning."

Look, it all makes the Bayeux Tapestry seem cutting-edge, but there's a wistful tone to Christopher Morahan's quaint production that has its own quiet pleasures. Simon Higlett's elegant design encompasses the full sweep of the seasons, as the trees in Smith's garden dry up and shed their leaves, while the walls of her house seem to blow away as if made of dandelion seeds. Inside and outside blend together; floral carpets and armchairs and all manner of pot plants make Smith's sitting room into a nature reserve.

It gives the impression that there's a peace to her kind of hermitage, even something entirely natural about it. If you mourn for Smith's solitudinous manner, for the timidity that prevents her from living life fully, she never seems to mind much herself. In fact, there's a low-key defiance about "this house of female habitation," for while Smith might not suit the hustle and hassle of the working world, she rejects it for a life that fits her just fine. None of us, in the end, can escape our own natures.

Stevie runs at the Hampstead Theatre until 18 April. Click here for more information and to book tickets.