Review: Roller (Barbican Centre)

Rachel Mars and nat tarrab explore roller derby in this year’s Oxford Samuel Beckett Theatre Trust Award winner

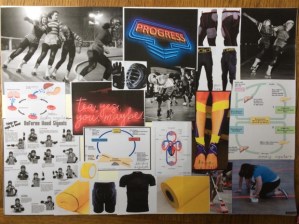

Roller Derby’s roots go back to the 1930s, but its modern incarnation originated as an all-female sport. Revived in the early 2000s, its rules were reconstructed by and for women. Roller holds it up as a beacon of feminism-in-practice.

Three years in the making, Roller still feels right on right now. Devised in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein revelations, Rachel Mars and nat tarrab’s exploration of roller derby has reshaped itself as a direct response: alive, kicking and only half-thought-through. For all its immediacy, Roller says very little.

Wheeled out on ladders in long black shirts, holding big black books, Mars and tarrab look like demon headmistresses or high priestesses. Speaking in unison, austere and foreboding, they declare the end of one era and the start of another. This, they intone, will be "a sudden lurch forward. There are millennia of injustices to put right."

Around them, a group of women in grey – women of colour, old and young, able-bodied and disabled – beaver quietly away. Together, they shake out a ring of yellow dust, unfolding a racetrack and doling out protective equipment. They talk of roller derby, but by not naming the sport, they could be describing a blueprint for revolution: women coming together to create their own space, establishing their own rules, training together and forming a team.

Mars and tarrab undercut the pomp of vengeful, intellectual feminism with humorous aplomb. Their double act disintegrates into bickering ego. When Mars threatens the front row, holding a metal pole over one spectator’s head, tarrab merely stands back in scorn. The quiet determination of the rollers around them looks stronger by far: constructive, collaborative and in control.

At 50 minutes, Roller‘s a slip of a thing; neatly done but, ultimately, rather innocuous. The notion that man-hating, power-grabbing feminism is not, after all, its ideal form; that feminism is not feminism if women replicate patriarchal norms – these are easy, trite statements, no matter how concisely illustrated onstage. They’re starting points, not conclusions; single sentence thoughts.

It’s all well and good, and not a little inspiring, to point to the collaboration and creativity of Roller Derby as a real (and radical) alternative action, but in doing no more than that, Roller stops short. It argues for grassroots community-led practice, yet, rather than working with roller derby teams for real, Roller employs actors to represent rollerskating revolutionaries on the Barbican’s London stage. No matter how hard it tries, it’s still all talk, no action; a group of feminist artists decrying feminism-on-high from their own position on-high.

Roller runs at the Barbican Centre until 2 December.