People, Places and Things review – Denise Gough leads a must-see return

Duncan Macmillan’s play is back in the West End

While you can’t improve on perfection, you can still surround it with such levels of excellence that its lustre seems magnified so that it shines even brighter. That was my main thought after watching again, after an eight-year gap, Denise Gough’s incandescent, career-defining performance in Duncan MacMillan’s mesmerising slam dunk of a tragicomedy about addiction and its ripple effects.

When Jeremy Herrin’s co-production for Headlong and the National first opened at the Dorfman in 2015 before transferring into the West End the following year, it felt, despite a strong cast, very much like the Denise Gough show. That’s not surprising given that with Emma, the formidably intelligent, self-destructively hedonistic actress at the core of People, Places And Things (“acting gives me the same thing I get from drugs and alcohol. Good parts are just harder to come by”), MacMillan has created one of the most challenging but exciting female lead roles in modern drama, and Gough inhabited her with such uninhibited conviction and raw power that it was hard for any of the peripheral characters to get much of a look-in.

Gough is no less astonishing now. If anything, her Emma is even more vivid in her wildness, her desperation and her charting of the highest highs and lowest lows. She’s certainly funnier: although there is nothing truly amusing about watching a human being fall apart while under the influence of alcohol and drugs, Gough’s Emma trying to put on a pair of trousers while absolutely out of her mind is sublime physical acting, and her acerbic wit that cuts through moments of unbearable anguish seems even sharper than before. She’s by turns captivating then terrifying, ferocious yet vulnerable, but never self-pitying: her hollow-eyed despair when she realises the damage she’s inflicted both on herself and on others sits in stark contrast to the bravado with which she defends her extreme partying, yet feels all of a piece with it. This remains a searing masterclass in acting, and a towering achievement.

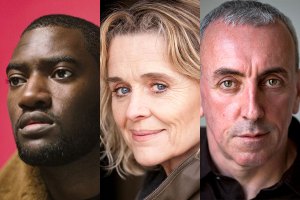

However, this return scores above its predecessors because, in two key but necessarily less showy roles, Herrin has now cast actors who are every bit as impressive as his leading lady. As Mark, the sympathetic addict further down his recovery journey than Emma, Malachi Kirby is so natural that it barely looks like acting, in a tender, truthful portrait of a human for whom it’s hard to tell whether his loneliness fed his addiction or vice versa. Sinéad Cusack plays the kind but uncompromising doctor who assesses Emma, then the therapist who tries to help her, then finally the mother so disillusioned and damaged by her daughter’s challenges that you can almost see the milk of human kindness draining out of her. Cusack invests each of these women with a breathtaking specificity and unshowy honesty, but is truly phenomenal in the latter role.

Kevin McMonagle returns as Emma’s father in a portrayal that has become more moving and quietly shocking since the original production, and Danny Kirrane delivers a lovely turn as one of key workers in the addiction treatment facility where Emma winds up. A large ensemble skilfully flesh out the other patients and, in a number of nightmarish choreographed sequences by Polly Bennett, alternate versions of Emma as she struggles to overcome her addiction. Andrzej Goulding’s unsettling video designs, Bunny Christie’s clinical tiled set (featuring audience members onstage as though taking part in a particularly elaborate group therapy session) and above all Tom Gibbons’ sound and Matthew Herbert’s music, both of which appear intended to cause acute physical discomfort at times, conspire to suggest a life tumbling out of control. Although Herrin’s staging is flashy and boldly inventive, it’s at the expense of the bruised and battered humanity at the heart of the script.

The play is a little baggy, especially in the first half where the group scenes, although terrifically acted, drag a bit, but MacMillan’s conflation of addiction and recovery with broader themes such as religion, bereavement, upbringing, and the compulsive nature of being a creative artist, is brilliantly done. So is the relish with which he has Emma describe the joy of that first hit of drug-induced dopamine, and the way the dialogue can turn on a dime from utter desolation to laugh-out-loud hilarious; even the newly added references to Brexit and Covid don’t jar, and the question of whether addiction is a valid response to a troubled world is an endlessly intriguing one. When the writing soars, it’s some of the finest work on any current London stage, reaching its apotheosis in a heart-stopping final almost-showdown between Emma and her parents, that plays out like something from a thriller.

People, Places And Things remains sensational but not sensationalist, a provocative, illuminating drama, and now, despite Gough’s repeated triumph, there’s more than one performance that lingers long in the memory afterwards. A painful pleasure, and a must-see all over again.