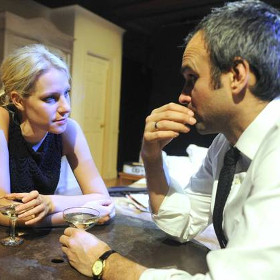

Little Black Book (Park Theatre)

Jean-Claude Carriere’s love story opened at the Park Theatre earlier this week (18 December 2013)

Suzanne likes her own company and reading Elle magazine. Jean-Jacques is a partner in a law firm and prefers the company of women, specifically women who listen to his limp compliments and act upon his disposable offerings of sex.

One morning, as he writes about last night's girl in his little black book, his rhythm is skewed by Suzanne – a relative stranger – who rushes in to his apartment, keen on bagging a place to stay the night. Three days later, and at this French play's close, Suzanne's still there, in an empty apartment, clutching what used to be Jean-Jacques most prized possession.

Little Black Book is a charming window into the plausibility of love and the recklessness of day-to-day life. Together and falling apart, these two somewhat fantastical characters gel via a bulk of both hilarious and saddening skits. Take Jean-Jacques' naive lessons in woo-ship: he sprays his apartment with a musky scent to encourage sex when girls come round, he tells Suzanne. Not that she's adverse to rogue moves. She slips in and out of clothes in seconds to encourage his wandering eye.

These two aren't built for resolve, nor does it particularly matter why they are bought together. They are merely images of heartache and confusion in a production that projects both the weighty concerns of the human heart, and the frivolity that helps us manage the pain.

And what a lot of fun heartache can be. Carrière's text is full of quick silliness and dizzying bombast, just as a play about a lady hijacking a lawyer's apartment should be. Moments of elementary mischievousness get grand smiles – in one of few scenes inviting the outside world in, Jenny Rainsford's Suzanne throws an ornamental Lizard out of the window and Jean-Jacques responds by chucking out her coat. Director Kate Fahy's staging includes a nicely measured nod to the fourth wall which is intriguing and a lot of fun.

This one-act piece is sprightly by any standard, but Fahy's buffed-up production adds just enough experimental flair – aside the competencies of both Rainsford and Gerald Kyd – to make this an adorable portrayal of the gameplay of lone lovers, thrillingly chasing each other in circles.