Len Johnson – Fighter (Greater Manchester Fringe Festival)

Colin Connor’s new play tells the story of “the greatest British middleweight never to be champion”

The Kings Arms is a flexible performance space and it's been transformed into a boxing ring. The cast of Len Johnson: Fighter enter with boxes and ropes and gradually construct the arena. It's a typical example of the commitment of all involved to a play that seems to be a labour of love.

Mancunian Len Johnson was born, in the early part of the 20th Century, to a white mother and a black father. Although his fighting abilities were widely acknowledged he was denied the chance to compete at championship level by racist policies that barred anyone not born of white parents.

Denied the chance to practice his vocation and inspired by Paul Robeson’s work with the Civil Rights Movement Johnson became involved in local politics and joins the Communist Party to fight for increased social mobility.

The play is a rich and exuberant experience; it has so many elements. The possibility of self-indulgence is a risk yet director Nick Birchill’s impressive control ensures clarity is maintained and audience attention retained. Mark Simpson’s evocative score, performed by the cast as the play progresses, adds to the sense of a community struggling to retain dignity in the face of overwhelming challenges. The casual racism that constantly occurs throughout gives a strong demonstration of the obstacles faced by Johnson and helps set the time and place in which events occur.

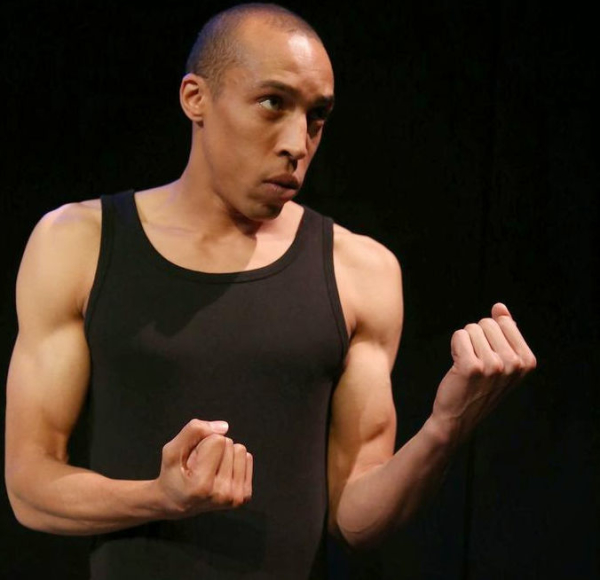

This is a faultless ensemble cast with some outstanding performances. Richard Patterson adds surprising charm to an embittered freedom fighter. The physical presence of Jarreau Benjamin, in the title role, brings authenticity to the play making it completely believable that the fighting abilities of Johnson were so great as to deter potential opponents from giving him a chance to compete.

Len Johnson: Fighter has many virtues, but subtlety is not one of them. The larger-than-life approach that works so well with the music is less successful with the portrayal of racists as pantomime villains cackling behind cartoon masks. Colin Connor’s script is full of passion but the mixture of personal and political histories does not always work. Connor does not risk the audience misunderstanding the points he wants to make. Issues that are already apparent from the scenes enacted are repeated in clumsy dialogue just in case they were missed the first time. Political points are hammered home in overlong speeches; the criticism, in a scene set in the 1960s, of Government reluctance to fund sports development echoes in the present day. Although there is no doubt that Johnson was sincere in his efforts to achieve change the play is coy about the extent to which he was successful.

The imaginative staging and fine performances make Len Johnson: Fighter a strong play but its impact is reduced by the nagging sense that, on occasion, the production slips into a lecture.