Holly Williams: Should we still favour writers over companies?

After experimental theatre company Forced Entertainment received the prestigious International Ibsen Award on the weekend, Holly Williams reflects on why there’s still a bias towards the literary in the UK

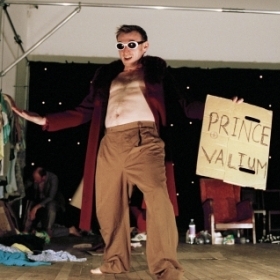

© Hugo Glendinning

Last weekend, in Oslo, the International Ibsen Award – which has been dubbed the Nobel prize for theatre, and is worth a whopping 300,000 euros – was awarded to Forced Entertainment, the Sheffield-based, experimental theatre company.

It’s kind of a big deal: it’s the first time the bi-annual award has gone to a group, not an individual; previous winners have included Peter Brook, Jon Fosse and Peter Handke. It reflects the high esteem the collective are held in across Europe – and rather shows up a disparity with our own theatre scene.

Over their 32 years performing together as a core company of six, Forced Entertainment’s devised, improvised, marathon, playful, serious work has been warmly embraced by theatres and festivals in mainland Europe, where they have an impressive reputation; here, they’re still seen as a bit fringe.

If a British playwright had won, there’d be a lot more fuss

And that’s surely to do with the way we think about theatre in the UK: the play is still very much the thing. We hold up individual genius writers, not companies; we celebrate famous plays, not processes of change, or places of exploration.

The theatrical landscape has, of course, changed since Forced Entertainment started making theatre in 1984; today, if you want it, there is plenty of devised work around – plenty of young companies doing startling things, and a few more seasoned ones that have also exerted staying power, influence, and global reach: think of Complicite, or Punchdrunk.

But, speaking to Forced Entertainment’s Tim Etchells ahead of their receiving the award, he suggested that the bias towards the literary is still entrenched in the UK. "Even if things have changed – and they have; we don’t have to have so many ridiculous arguments as we used to – deep down, there’s still a lot of power around the authorial position. The whole way Forced Entertainment’s work communicates is still in a state of friction with the scene here in the UK."

The bias towards the literary is still entrenched in the UK

I suspect that if a British playwright had won this award, there’d be a lot more fuss being made about it. If it had gone to, say, David Hare or Tom Stoppard, there’d be hefty career-retrospective profiles appearing, Britain’s contribution to global theatre being shouted about. But we simply don’t have quite the same framework for supporting companies, or celebrating devised work, as we do for individual writers and directors. It probably starts with the – understandable! – dominance of Shakespeare, but the canon is defined by plays and playwrights still (and still mostly deadwhitemales, of course).

And think of own glitter-encrusted awards ceremonies. If you want to win a theatre award in the UK, it really helps to either be already very famous, or perform in or direct an already very famous play. We tend to celebrate excellent productions of plays we’ve already heard of at big theatres, not the weird boundary-pushing stuff round the edges. If you want to win best actor, give us your tragic Shakespearean hero; for best actress it helps to do, well, an Ibsen. Edgy directors can win audiences and gongs if they offer fresh visions… of already classic plays; an Arthur Miller, say, or a Chekhov.

There are obvious practical reasons for dominance of the script: you can read play texts, after all, which gives them both reach and permanence. No matter that they’re not the finished thing, you can still ask a class of 13 year-olds to trudge through Macbeth or get undergrads to grapple with Pinter. You have the bones there; you can analyse it. It’s harder to teach a show that finished 20 years ago (although many excellent academics do try). Harder to prove to anyone it really was brilliant too – although isn’t that partly why we have criticism and awards, to celebrate the ephemeral in the moment it passes, to say ‘this was valuable’?

Obviously a thriving theatre culture benefits from having both types of work, anyway. I love a beautifully written playtext, think Britain’s current new writing scene is frequently thrilling, and enjoy what feels like a constant stream of really interesting new interpretations of classic plays. All good stuff. But perhaps we could also learn from our European cousins, and be a little less enthralled at the idea of the singular artistic vision, and a little more celebratory of the collective, the experimental, the ephemeral.