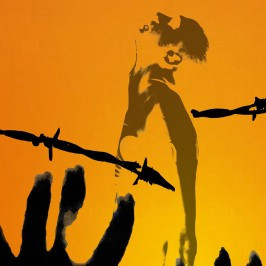

Guantanamo Boy

Brolly Productions’ adaptation of Anna Perera’s novel opened this week at the Half Moon Theatre

Khalid (Antonio Khela) is an ordinary 15 year old from Rochdale. He’s keen on football, enjoys joshing with his friend, has his adolescent eye on a pleasant white girl and finds his sari-clad, gently pushy mum a bit much. He is also obsessed with very sophisticated violent computer games which are his downfall when his mother drags him to India to visit family.

Picked up as a suspected terrorist, he ends up imprisoned in Guantanamo Bay. It’s a slick and powerful, theatre-in-the-round, four-hander adaptation of Anna Perera’s fine, still-topical novel from Brolly Productions.

Rachana Jadhav’s clever set uses movable screens, sometimes diagonally across the corners of the playing space and sometimes bisecting the space to evoke prison bars. At each end are screens on which Khalid’s games are played out and, later we get nightmarish, hinted at snatches of 9/11 footage to denote the overriding concern of the agent at Guantanamo trying to torture the truth out of Khalid. And there’s a great deal of deliberately very uncomfortable noise.

This is intimate, almost televisual theatre and Khela is good as the distraught, anguished, terrified Khalid. The downhill spiral followed by the final return of a damaged-for-life boy to Rochdale is well handled too. He has a very expressive face. The versatile Edward Nkom is enjoyable as the Rochdale schoolfriend and the two Guantanamo guards – one half-sympathetic and the other a merciless obeyer of orders. The water-boarding sequence is especially chilling. Roisin O’Loughlin is cheerfully engaging as the Rochdale girl and suitably cold and manipulative as the American interrogator. Bhawna Bhawsar makes a pleasing fist of the stereotyped Indian mother and doubles as Abdul, a fellow Guantanamo prisoner.

So there’s a great deal to admire in this show which asks very searching questions about human rights, but there are serious flaws too. All characters use strong accents, in some cases several different ones, and they’ve been directed to speak very fast, inevitably always with their backs to part of the in-the-round audience – against a sound track which is often very loud. The result is that much of the dialogue is lost. Only Bhasar, with her carefully enunciated Indian accent, is fully audible but she fails to put enough dramatic vocal distance between her two characters so even her work is not fully satisfactory.