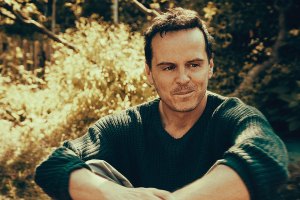

Vanya review – Andrew Scott’s solo tour-de-force in the West End

Simon Stephens adapts Chekhov for the West End – with Andrew Scott taking on every role

Wow. This astonishing version of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya is a tour-de-force by the actor Andrew Scott in which he takes on eight roles while all the time preserving the perfect balance of comedy and tragedy that makes this the most humane of plays. What could have felt like a gimmick becomes a revelation.

What’s so magical about it is its delicacy. You imagine in advance that in order to embody so many different characters from the unhappy title figure, to his aged mother, to a crusading doctor, to a glamorous siren, and a plain lovelorn niece, Scott will resort to a lot of busyness, showing his range by leaping around the stage, putting on funny voices.

Yet it is the subtlety of the storytelling that is so remarkable. You can hear a pin drop as he morphs gracefully between each participant, lowering his voice slightly as the doctor Michael, drawling in sunglasses as Vanya (here Ivan), fingering a necklace as the indolent Helena and wafting a cloth as the resolute Sonya. He makes you lean into the narrative that is unfolding, feeling its familiar lineaments in a new configuration, understanding aspects of Chekhov as if for the first time.

Scott is credited as a co-creator alongside writer Simon Stephens (with whom he has previously worked on Sea Wall and Birdland), director Sam Yates and designer Rosanna Vize and the entire proceedings emit a sense of a group of people coming together to work very carefully on something they love.

Stephens’ writing is as refined and understated as Scott’s performance, full of glancing jokes – an imaginary dog that suddenly appears, a character supposedly sitting by the side of the stage, forgotten – and easy language that lands beautifully. It acts as a gloss on Chekhov even as it honours him.

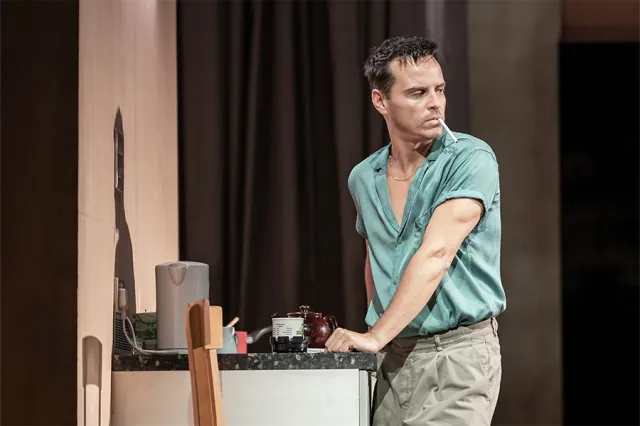

He sets the narrative here and everywhere; Vize’s set is modern and practical, with a kitchen where Scott can turn off the house lights with the flick of a switch (the opening moment) and put on a kettle to make tea. The names of the characters are altered to suit a new setting: Marina is Maureen, Astrov becomes Michael, Yelena is Helena.

But there’s a theatricality embedded in the staging too. A curtain at the rear is swept back to reveal a wall of mirrors; a plywood door centre stage enables Scott to play with arrivals and departures, leaving as one protagonist and entering as another. A swing hangs on one side. It’s the languid Helena’s favourite seat and sways gently, suggesting her presence even as Scott is playing one of her admirers.

As James Farncombe’s lighting suggests the passing of the days, the movement (by Michela Meazza) manages at moments to turn Scott into two people, the twitch of a shoulder or the folding around himself of an arm suggesting an embrace or – when Michael and Helena acknowledge their feelings for one another – full-blown passion. Yates’ direction is as precise and thoughtful as everything on display, constantly switching the focus, letting different figures take centre stage even as Scott plays them all.

Scott’s timing, the way he can pivot in a moment between voices and characters, is spellbinding. It means he wrests every ounce out of the comedy of Ivan’s despair when he fails to shoot his ghastly brother-in-law Alexander, transformed from a scholar to a “generational defining film-maker”. But he and Stephens also make you realise how much his loathing for the man is rooted in his love for his dead sister, whose piano occasionally plays in the corner, conjuring her spirit.

It’s one example of how deeply Stephens has thought about the play. Alexander’s insistence that the piano should stay silent is contrasted with Helena’s wish to play it; he distorts people by his egotism. But the other quality of the adaptation is the way in which it suggests the characters are united by their ability to suppress emotion, to deny themselves life. The melancholy thread that runs beneath all Scott’s characterisations tugs at the emotions of the piece.

The final scene, in which he becomes sad Sonya, her hopes of love lost, comforting Ivan with the thought that this unhappiness too will pass and “we’ll see the whole sky full of diamonds” is quietly overwhelming. It is so full of feeling and empathy that you cannot quite believe that you are actually watching a single man sitting alone, holding the arm of a chair. It is a great achievement.