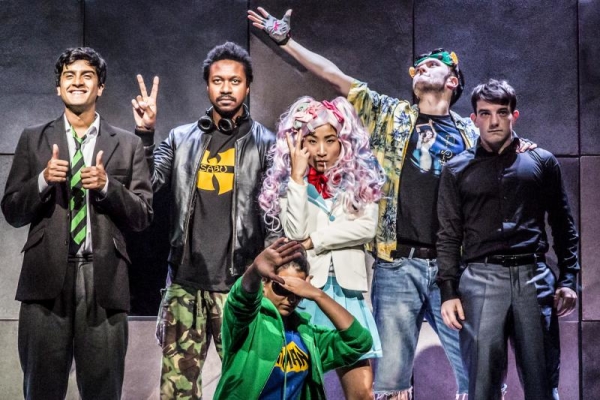

Teh Internet is Serious Business (Royal Court)

The Royal Court’s latest anarchic offering tells the story of Anonymous and LulzSec hacktivists

This is for everyone. Or so Tim Berners-Lee might have intended when creating the World Wide Web, but the internet has long since been colonised by governments, corporations, religions and security services. Which is where Anonymous come in.

The Royal Court’s latest offering in its revolutionary themed season charts the rise and fall of the infamous hacktivist network, as well as its splinter group LulzSec. Between them, these anonymous groups of hackers infiltrated websites including Fox, PBS and the CIA, as well as breaking down the internet restrictions hampering Tunisian rebels. The revolution might not be televised, but screens could well play a role in its coordination.

Tim Price‘s fictionalisation of the hackers’ true story is just as anarchic as its subject matter, coding the narrative of core Anonymous and LulzSec members into a fast-paced, frantically clicking swirl of online information. At the centre of it all are Jake (Kevin Guthrie) and Mustafa (Hamza Jeetooa), two socially awkward teenagers forcing corporations to their knees from their bedrooms and basements. While sharing funny videos.

If there’s one rule of the internet that Hamish Pirie‘s production abides by, it’s that "everything is funny all the time". Sure, there’s political motivation behind much of the hacking, but the movement all started from a quest for lulz. The comic absurdity of rendering online environments IRL is a device that Pirie and designer Chloe Lamford stretch as far as it will go, eschewing screens and technology in favour of live performance’s own arsenal. Sequences of code become surreal choreography, while memes pop up left, right and centre in hilariously physicalised form.

The one problem with all of this is the same one that tainted Anonymous: misogyny. One of the "rules" of 4chan, to which Anonymous’s origins can be traced, is that "there are no girls on the internet", while casual and occasionally brutal sexism runs right through the movement. Teh Internet is Serious Business does acknowledge and to an extent trouble this uncomfortable fact, but the excitement and energy of the production soon sweep us up in its irresistible momentum, problematically leaving this niggle far behind.

That’s not to say, however, that Price and Pirie are not acutely aware of the many issues thrown up by the story they are telling. The production is complicatedly ambivalent about the mask of anonymity, illustrating both its power and its ugliness. The hackers’ central resistance to online censorship, meanwhile, stands up for the freedom of abusers as much as protesters. The question is posed: is it possible to defend internet culture without defending the bad as well as the good?

But in spite of the title, Teh Internet is Serious Business is not all that interested in seriousness. Instead, the big ideas sit underneath a gloriously messy and completely intoxicating riot of stage images, best summed up by Lamford’s visual metaphor of a big, colourful ball pond. And perhaps there is something more to the internet’s ceaseless, mocking laughter. As Jake (aka online handle Topiary) says, "you can’t make the internet feel bad". And for all its pitfalls, there’s something kind of radical about that.

Teh Internet is Serious Business runs at the Royal Court until 25 October