Review: The Visit or The Old Lady Comes to Call (National Theatre)

Tony Kushner’s adaptation of the Friedrich Dürrenmatt play is now running in the Olivier at the National Theatre

© Johan Persson

Lesley Manville stands stock still at the centre of the Olivier's vast stage, smoke swirling around her, leaning on a cane and almost imperceptibly tilting her chin as she listens imperiously to the grovelling around her. She looks – as Francois Mitterand once said memorably of Margaret Thatcher – like a cross between Marilyn Monroe and Caligula, soft sensuality tempered by a spine of steel. Her legs are made of metal which means she struts rather than walks as she advances on her prey. Her voice, when she speaks, is husky yet commanding. She owns the world.

Her performance as the world's richest woman, Claire Zachanassian, is the principal reason to rush to the National Theatre's revival of Friedrich Dürrenmatt's The Visit or The Old Lady Comes to Call. It is quite simply spellbinding. She beautifully, and with immense sensitivity, hinting at all sorts of repressed emotion within, charts the progress of Claire who has returned to seek revenge on the town – and the man – who spurned her when she was a pregnant 16 year-old.

She comes back to the unattractively named Slurry, bankrupt and desperate for a cash injection, to offer a Faustian pact. She will give the place and its inhabitants a billion dollars, but in return someone must kill Alfred Ill (Hugo Weaving), her teenage lover who persuaded his friends to perjure themselves and so deny the paternity of his daughter.

In the hands of adaptor Tony Kushner, famous for Angels in America, Dürrenmatt's relatively spare, savage satire about post-war reparation, which premiered in 1956, becomes a whirling, expansive attack on American consumerism, and the way the debt needed to buy beautiful, colourful, pointless things has undermined all moral value. It's now full of his soaring, compelling language, and great speeches about love, sex, money, politics – the whole damned thing.

But it is now also three and a half hours long which, even with two intervals, is at least half an hour too long for what is in essence a fairly simple latter-day myth in which Claire is cast as an implacable fury, determined to get justice whatever the cost. There's not much doubt she will succeed, nor do you much care about any of the characters who are clearly not going to stop her, once they start buying shiny shoes on credit. All that matters is the unfolding.

Jeremy Herrin's assured, vivid production does its best to pull us along. He fills the stage with crowds, shaping tableau that slip in and out of focus to the sound of Paul Englishby's bluesy score, a melancholy soundtrack played live by a band in a (distractingly) lighted box above the stage. Vicki Mortimer's set reveals her as the queen of the Olivier's revolve, making brilliant use of its open spaces, setting a gantry above for Manville to peer down on the action. Paule Constable's lighting and Moritz Junge's costumes (steadily becoming more glamorous as the lure of capital takes hold) are perfect. The production looks a million dollars, with high-heeled, black-tulle'd female coffin carriers stalking the space, followed by a chilling, blinded, vaudevillian double act.

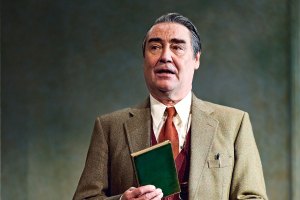

But there's an awful lot of everything and when Manville is not centre stage, the action feels curiously airless. There is excellent support however from Sara Kestelman, Nicholas Woodeson and Joseph Mydell as the town elders who chart the inevitable decline from moral righteousness to murder. They know, in different ways, that it is wrong to be bought but none can see any way of stopping money's frightening siren call.

As Alfred, Weaving too goes on a journey; you see his guilt from the beginning, as he resists his friends' attempts to make him use his old bond with Claire to get cash. He knows that he failed to do the right thing, and guilt eats him from the inside even as fear of his death consumes him. The final scene in the woods between him and Manville, where they sing together, and she explains her vision of love is transfixing; everything after it feels like empty noise.