Review: The Welkin (National Theatre)

© Brinkhoff-Moegenburg

Lucy Kirkwood is a playwright of dazzling ambition. Her themes range high and wide. Her breakthrough play Chimerica (in 2013) tackled Chinese American relations, Mosquitoes used nuclear physics to atomise the ties that bind a family, the magnificent (and under-valued) The Children faced up squarely to nuclear annihilation and climate change.

Now in The Welkin – the title is an archaism meaning the sky or the heavens – she has created a historical drama that tackles women's lot in life down the centuries within the format of a courtroom drama. Set on the borders of Norfolk and Suffolk in 1759, the year Halley's Comet blazed across the sky, it pins its story to a historical fact – that when a female prisoner who claimed to be pregnant was sentenced to hang, a jury of 12 matrons could be empanelled to judge whether she was really with child because 18th century justice did not want to kill the innocent baby.

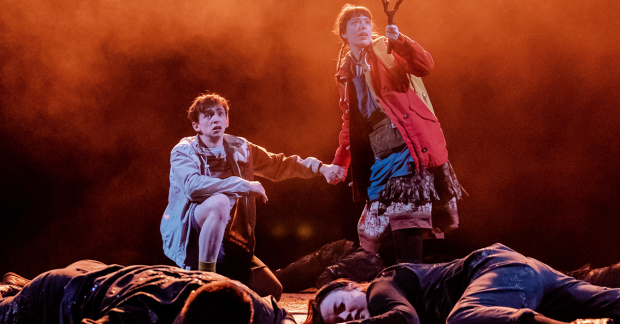

Kirkwood's fictional prisoner is Sally Poppy, a foul-mouthed, broiling teenager who dared to raise her eyes from her brutalised life of poverty and drudgery and dream of a different adventure. She has been found guilty – with her lover – of the particularly violent murder of a rich man's child; she will hang unless the matrons judge her pregnant.

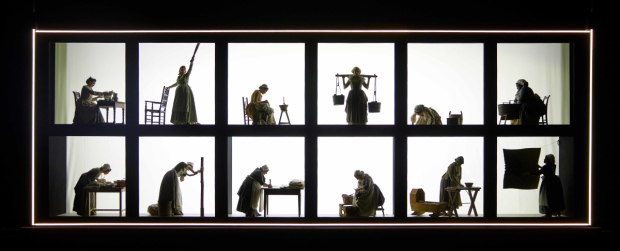

The play opens with the most stunning image of Housework – each of the twelve women silhouetted in a square box of light carrying out, repetitively and endlessly, their mundane, back-breaking tasks such as drying washing at a wringing post or beating a rug. This is the background from which the women are to be locked in a grey, high-ceilinged room, freed from domestic responsibilities but without "meat, drink, fire or candle" in order to examine Sally. Outside a crowd bays for her blood.

© Brinkhoff Moegenburg

Bunny Christie's wonderful designs, illuminated by Lee Curran, make them look like the background figures in Hogarth print; Kirkwood's writing swiftly and deftly differentiates them. Their natural leader is Elizabeth Luke (Maxine Peake), the local midwife who, like Henry Fonda in Twelve Angry Men, places herself firmly on the side of the defendant and who relishes the rare opportunity for women to have a hand in the course of events in a world where is dictated by men. She's a proto-feminist, railing against the patriarchy. "Nobody blames God when there is a woman to blame instead," she remarks wryly.

But the woman nominally in charge is Haydn Gwynne's Charlotte Cary, widow of a colonel, a visitor to the parish. Around them cluster a group of local women, whose status and class is varied; one worries about planting leeks, another about her hot flushes. One is barren, one has had 21 children. Talking in a mixture of archaic and contemporary language, the details of their lives float to the surface.

Kirkwood allows themes to rise and fall away: what is true innocence, how important are social conditions in determining character, who controls and who understands women's bodies, what does it mean to live in a world where the responsibility for tidying up falls to you, even when you are supposedly in charge of determining whether someone hangs. The trust placed in a male doctor prompts a discussion of contraception and the unreliability of the withdrawal method – "I always kept a piece of brick in a handkerchief under the bed," Jenny Galloway's pragmatic Judith Brewer remarks. "If you time your strike right you can save yourself a lot of trouble in the long run" – and of the fact that women's bodies are less understood than the comet about to flash through the skies.

Above all, there are stories, unfolding slowly, sometimes containing revelations, feeding the general texture of these women's histories, sometimes pointing contemporary relevance. Under James Macdonald's careful, clear-eyed direction the narrative is consistently engrossing, and utterly compelling.

There are problems: the accents adopted lead to a certain degree of incomprehensibility, particularly of Ria Zmitrowicz's angry Sally. Elizabeth's righteous preaching, although delivered with all Peake's habitual passion, sometimes merely underlines conclusions we could have drawn for ourselves. The life of the play lies in the vividness of the portrait it paints; it doesn't always need quite as much exposition as it gets.

But it is a brilliant, brave, bold and intelligent three hours in the theatre. It is, for all the seriousness of its subject, often very funny yet at the close, profoundly moving.