Matt Trueman: My top ten shows of 2015

WhatsOnStage critic Matt Trueman picks the shows he loved in 2015

For a while now, there’s been talk of a golden age for British theatre: a sense that it’s firing on all cylinders. You know what? I think it might, finally, be time to admit that it’s borne fruit. Having resisted the urge to declare vintage years in the past, this year I’ve seen more top-drawer productions than ever before – more, in fact, than I can fit into my top ten (in no particular order) below.

Force me to put my finger on why and I’d point to the interplay of script and production; a desire to push the possibilities of a play in performance, to find a unique form that brings out the main gesture of a text. Time and again, productions have risen to the challenge of playtexts. If theatre is as popular as ever (in London at least), it’s because it’s doing something no other medium can.

THE ENCOUNTER, Edinburgh International Festival, August.

If Fergus Linehan rejuvenated the Edinburgh International Festival in a shot, The Encounter was the jewel in the crown of his first year. An adventure story to sink into, about American photojournalist Loren McIntyre, lost in the Amazon with an indigenous tribe, it was as much about the telling as the tale itself.

This was Complicite‘s old magic given a technological twist. Nobody makes something out of nothing like Simon McBurney. In the past, objects have come to life: books as birds, bamboo sticks as buildings. Here, he built the Amazon out of sound: water bottles crunched like leaves underfoot, crisp packets rustled like rain, whoops and whistles filled the forest with birds. Your head housed a whole ecosystem.

All of McBurney’s favourite subjects were in the mix: the fascination for anthropology he inherited from his father, a philosophical enquiry into the nature of time and technology, a profound sense of the importance of stories. It all made a heady, intoxicating two hours; form and content entwining perfectly. Just as McIntyre fell out of time, so did we. The show of the year, hands down.

The Encounter runs at the Barbican from 12 February – 6 March 2016.

JANE EYRE, National Theatre, September.

Imported from the Bristol Old Vic, Sally Cookson‘s staging of Jane Eyre transformed Charlotte Bronte’s novel into a thrilling piece of total theatre. Running along to Benji Bowers’ gorgeous folk score, this was Jane Eyre as feeling, carried by colours, rhythms and bodies in space. Madeleine Worrall was brilliant as its tough but timid heroine; the gruff Felix Hayes, a human sigh as Mr Rochester. Revisionist too: Melanie Marshall's slow, sorrowful version of Gnarls Barkley’s 'Crazy' restored Bertha some dignity.

Jane Eyre runs at the National until January 10.

ORESTEIA, Almeida Theatre, May.

Greek tragedy to rival anything on HBO, Robert Icke‘s Oresteia turned Aeschylus into a contemporary dramatist. How to shake off the sight of Angus Wright‘s Agamemnon cradling his young daughter while the poison inside her takes effect? Or of Lia Williams, as Clytemnestra, smiling the thinnest of smiles to the cameras as her husband, the man that killed her youngest child, returns from war? Or of Luke Thompson’s dead-eyed Orestes in the dock having completed the cycle of revenge? Stark, ritualistic and potent, Oresteia was theatre at its most exhilarating.

© Manuel Harlan

IPHIGENIA IN SPLOTT, Edinburgh fringe festival, August.

Gary Owen gave us one of the year’s trickiest dilemmas in Violence and Son, luring us into sympathising with an inadvertent teenage rapist. But it was this extraordinary monologue, an armour-piercing attack on austerity politics, that really dazzled. Set in a shitty part of Cardiff, getting shittier as the cuts set in, Iphigenia in Splott introduced us to Effie – a hard-drinking, fast-talking, in-yer-face teen – then watches as her heart breaks again and again. Devastating – and on at the National next month. Don’t miss it.

© Mark Douet

Iphigenia in Splott tours the UK in 2016 and runs at the National Theatre from 27 January.

FIREWORKS, Royal Court, February.

Six months after the latest Gaza war, the Royal Court brought Palestinian playwright Dalia Taha’s debut to its upstairs studio. It gave us a snapshot of life under shellfire, juxtaposing the war-games of children with those of adults. Full of shattering moments – families watching rockets like a fireworks display – it grew in force in Richard Twyman’s claustrophobic production, which played out under Natasha Chivers’ stuttering, flashbulb lighting. I found it sweltering.

© Helen Maybanks

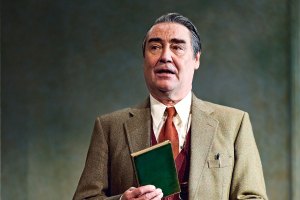

THE FATHER, Tricycle Theatre, May.

The genius of Florian Zeller‘s drama was to let us experience the confusion of dementia for ourselves. Between two scenes, Zeller shuffled the pack: Andre’s daughter gets replaced by a second actress and so seems a stranger; her husband and ex-husband trade places freely. Miriam Buether set went missing; desks and chairs disappearing like lost keys. A drama built on quicksand, you lose your grip on the play’s reality. Add Kenneth Cranham at his very best – gruff, flirtatious, charming and disarming – and The Father became unforgettable.

(c) Simon Annand

CARMEN DISRUPTION, Almeida Theatre, April.

I’m still not sure what to make of Simon Stephens‘ Bizet-shuffle, except that it flayed the skin off me. A kind of performance poem, dense and overwhelming, it felt like a raincloud of contemporary ills: inequality and amorality, ennui and anomie. Its revolving cast – cabbies and rent-boys, opera stars and bankers – lost themselves in cities, in phones, in money, in transit, in sex and in themselves, and Michael Longhurst and Lizzie Clachan turned it all into a gold-gilt, fin-de-siecle, operatic spectacular.

© Marc Brenner

SMOKE AND MIRRORS, Edinburgh, August

This late addition to the Edinburgh Fringe was circus at its most excruciating. Not because Codhi Harrell and Laura Stokes contorted themselves into impossible configurations, but because it was so emotionally raw. Stripped out of office suits, they played it in plain white pants; all the better to see joints bent backwards and muscles overstretched. Stokes walked on the tops of her feet; Harrell hung off a trapeze, distant and dejected. Two bodies – and two people – pushed to breaking point.

THE CRUCIBLE, Manchester Royal Exchange, September.

I missed Yael Farber’s brooding Old Vic Crucible last year, but Caroline Steinbeis’ stark, insistent production for Manchester Royal Exchange was recompense enough. It wasn’t just that she stripped it back and modernised it, a la Ivo van Hove, it was that she pushed Miller’s play to its max, made it shrill and enervating as a car alarm. With Salem’s teenage girls in bright pastel colours, she tapped into the heart of the town’s fear: the vitality, and sexuality, of young women.

LIBERIAN GIRL, Royal Court, January.

What a year it’s been at the Royal Court Upstairs. One of London’s smallest spaces, it’s nonetheless crammed in the world – North Korea’s in residence at the moment – and challenged its audience again and again. Former usher Diana Nneka Atuona’s debut was a rampage through Liberia’s civil war (as was the brilliant Eclipsed at the Gate), following Juma Sharksh’s child soldier in disguise; a girl betraying her sex for her safety. Matthew Dunster‘s promenade production – quickfire, forceful, unblinking – was extraordinary, start to finish.

© Johan Persson