Review: The Winslow Boy (Chichester Festival Theatre)

A revival touring production of Terence Rattigan’s play stars Aden Gillett and Tessa Peake-Jones

It’s hard to imagine that 60 years ago, obituaries were being read for Terence Rattigan’s dramatic output. Deemed old fashioned and out of date by the start of the '60s, his plays nevertheless demonstrate remarkable resilience – particularly so at Chichester, where in the last decade alone no less than six revivals of his work have been staged.

Why the resurgence? The main reason is the underlying quality of the plays and the penetrating insights into the human condition. Where Rattigan is especially strong is in plays like The Winslow Boy, where the personal becomes the political. The story of Ronnie Winslow and the fight to clear his name after being expelled from naval college for theft is about a family’s willingness to make every sacrifice in the fight. Rattigan makes the point that it’s for liberty and a fight against the "despotism of bureaucracy" but underlying it is the admission that this comes at a cost to the family.

Rachel Kavanaugh’s handsome production captures the contrast between the wider struggle and the damage that can be wrought by an obstinate fight.

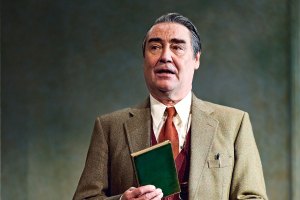

At the heart of the play is Aden Gillett’s Arthur, Ronnie’s father, believing passionately in his son and railing against injustice. Gillett transforms himself from a slightly sardonic pillar of the establishment to a single-minded striver for justice, sacrificing his wealth, his health and his family’s well-being to his struggle.

We’re never quite sure whether we’re admiring of Arthur’s fight or worried for the lack of empathy he’s showing to the rest of the family. Tessa Peake-Jones‘s Grace makes clear that her thoughts are only for her son and neatly captures the emotion of a mother who can see that her family is suffering.

The best performances come from Dorothea Myer-Bennett as Ronnie’s sister, suffragette Catherine and Timothy Watson’s Robert Morton, the QC hired to lead the legal fight. It’s a fascinating contrast: while Arthur’s support for Ronnie comes from familial obligation, she sees the fight to clear his name as part of a wider struggle. Burning with radical fire, Catherine is the emotional heart of the play and Myer-Bennett captures her spirit perfectly.

Morton is equally passionate about the case but Watson’s icy veneer is a mask for the underlying desire to right an injustice. The interplay between Kate and Morton is excellently handled and the hints of a burgeoning romance between the pair are subtle.

There are assured performances all round and Misha Butler as the wronged Ronnie makes a strong stage debut, while Soo Drouet makes for a lively parlour maid, Violet.

It’s Violet, in fact, who delivers the speech that announces Ronnie’s name has been cleared: it’s a mark of Rattigan’s genius that the vital scene is not in the hands of one of the lead characters, because the dramatic effect is that much greater. But then, this is a play whose themes are a fight for justice and abuse of political power and yet does not have one scene in a courtroom or parliament. The fact that all the action takes place in a single drawing room doesn’t dampen the impact one bit.

This is another triumphant Rattigan. I’m already looking forward to the next one.

The Winslow Boy runs at Chichester Festival Theatre until 17 February and then tours the UK until 19 May.