Review: Girl from the North Country (Gielgud Theatre)

The music of Bob Dylan returns to the London stage before a stint on Broadway

© Cylla von Tiedemann

Conor McPherson's musical, based on the discography of Bob Dylan, first premiered in 2017 at the Old Vic before transferring to the West End for a limited season. Now it returns to the West End with an almost entirely new cast, sandwiched between a stint in Toronto and the show's Broadway debut.

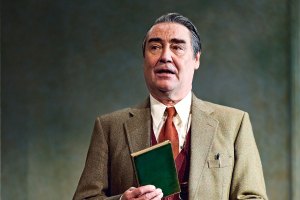

Set in the town of Duluth, Minnesota (Dylan's birthplace) in the grip of The Great Depression, we are introduced to a host of characters who come to reside in a shabby guest house run by Nick Laine (Donald Sage Mackay) and his wife Elizabeth (Katie Brayben, in a fine performance), who suffers from dementia. Other characters passing through include the Laine's adopted pregnant daughter Marianne (Gloria Obianyo), wrongly-accused boxer Joe Scott (Shaq Taylor) and Nick's lover, widow Mrs Nielsen (Rachel John, beautifully understated). For an unexplained reason, the show is narrated by smooth-talking Dr Walker (Fredy Roberts).

McPherson cleverly chooses tunes from Dylan's back catalogue that ensure it's not just a 'greatest hits' jukebox show, and his book allows the numbers and story to have a conversation with each other. Selecting songs spanning from 1963 to 2012, the music is played with only 1930s instruments, acting as close-ups on each character's state of being. As someone who isn't a Dylan devotee, this focus is a great way to become acquainted with his work, though to an unfamiliar ear the songs do sometimes begin to sound the same.

As a musical it's pretty form-breaking: the performers sing into microphones – towards the audience rather than other characters. A particular highlight is Obianyo's smooth performance of "Tight Connection to My Heart". Furniture moving during songs can feel clunky and unnecessary, but when the back of Rae Smith's set opens to reveal vast grey landscapes it's rather breathtaking. The overall soundscape is so beautiful it's very easy to simply let it wash over you.

It's not a fun or funny story at all – the show is held together by the thread of pain running through it. It appears circumstantially – the racism and misogyny of the time – as well as through death, illness and financial troubles. It's so embedded into the script that it feels uncomfortable to hear laughter when the elderly Mr Perry continually proposes to Marianne, or jokes about her looking young. A dead boy appears in a white suit and sings, which is a bit much. Later, when Marianne calls Perry out as a predator, there are some rightful agreeing murmurs from the audience.

Perhaps the largest flaw is that despite a strong ensemble cast it's difficult to fully connect with any one story, as there are a few too many to allow them room to fully develop. But this show is definitely about the music, and it should be seen for the performances alone.

In the final scene, the Laine family dine whilst the rest of the cast are silhouetted behind them. An image of what could be, of hope even in the darkest time. It's a striking ending, and perhaps one we need right now.