Review: A Museum in Baghdad (Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon)

Hannah Khalil’s story examines a museum opening and reopening after 80 years

© Ellie Kurttz for RSC

In 1926, a formidable British archaeologist named Gertrude Bell was responsible for opening a museum of antiquities in Baghdad. It came off the back of many years' work at the forefront of setting up the new state of Iraq and was, in that sense, symbolic of her achievements in preserving and protecting history.

Subsequently, Bell was all but written out of the narrative – not least because she was a woman. Writer Hannah Khalil, having discovered this story and the parallel one of the same museum reopening 80 years later after the Iraq war, saw a play in it. After working with director Erica Whyman, dramaturg Pippa Hill and David Grieg – artistic director of the Royal Lyceum in Edinburgh – Khalil's offering is now on display to the public in Stratford, where it runs before an outing next spring at London's Kiln Theatre. There's an old joke about a camel being a horse designed by a committee: A Museum in Baghdad suffers a similar disadvantage.

There's nothing wrong with the experimental form, and the twin threads of narrative from 1926 and 2006 run pretty seamlessly in tandem. Ditto abstract and impressionistic theatre, challenging the audience to do some thinking and bring their own interpretations to the party. The problems begin when there's little with which to engage, and a script that lacks momentum or drive.

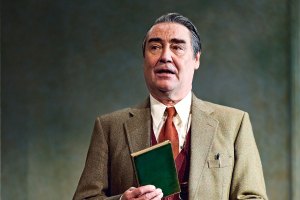

So we get a confident Bell in the shape of Emma Fielding, balancing the demands of the new Iraqi king with the pull of the British overseers, represented by the British Museum's Professor Woolley – a fine performance from David Birrell. But we have little sense of what has propelled her to this curious existence in the desert, nor why she will, within a few months, take an overdose of sleeping pills. Instead she's a mouthpiece for the cause of archaeology, at one point even delivering an actual lecture on why museums are so important.

In the 2006 iteration, another museum director, the brittle but clear-eyed Ghalia (Rendah Heywood), has returned from exile in London to run the place, only to find her local subordinates are less interested in the artefacts than in their daily survival. But again, there's not enough depth to any of the characters to build empathy as they drift verbosely towards their respective openings without any real dramatic impetus.

The production values are high and considerable work and effort has gone into putting the museum on stage. There's some sumptuous underscoring by Oğuz Kaplangi that generates a sense of atmosphere, and Tom Piper's design looks suitably dry and dusty. But these are not two adjectives you'd want to be attached to a new work intended to foreground a forgotten woman's place in history.