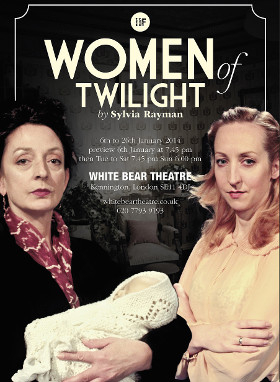

Women of Twilight (White Bear Theatre)

Sylvia Rayman’s play centering around a home for single mothers returns to the White Bear Theatre following a run in October

Sylvia Rayman's all-women play, a seldom-seen work from the early 1950s, is slowly harrowing to watch.

The production, which returns to the White Bear after a run in October, is played out entirely in the cramped, unwholesome sitting room of a shelter for desperate single mothers, and bears witness to their suffering, much-ignored at the time.

The home, where women are slept three to a room, the food is bad and the childcare worse, is the domain of landlady Helen Alistair (Sally Mortemore). A mixture of Dickensian moral front and Cruella de Vil, she calls herself a philanthropist but swindles her guests, neglects their children and does her best to convince them they are to blame.

The arrival of a well-spoken new guest, Christine, played with charm and empathy by Elizabeth Donnelly, introduces us gradually to the bleak situation she will come to share with a host of others.

From her initial surprise at sharing a room, to learning she must bribe Mrs Alistair in order to eat properly, to finding out how babies in the house are mistreated and allowed to die, through her we learn the true bleakness of the women's situation.

But sadder stories are to come – one guest, Vivianne (Claire Louise Amias), spends the play suffering through her boyfriend's murder trial and hanging. Things can always get worse.

The play – called 'hysterical' at the time – does not seem melodramatic now. There is no shortage of tears, but the outbursts held back are just as affecting. Many desperate exchanges are played with no more than the hint of a tear glistening in an eye.

Indeed, a sort of Blitz spirit punctuates the gloom, as the girls rally round each other in hardship and smile through the sadness. There are even moments of humour, particularly from Veronica (Amy Compyer), a Hermione Granger figure fallen on hard times.

To begin with Jess, a forthright east London gal, and practically a lifer in the guesthouse, is also a source of cheer, but this sours as her links to Mrs Alistair's corruption become clearer.

The women's struggles with their landlady, their men and their children swell to a crescendo for the final scenes – a procession of deeply sad moments which threaten to shake even such a blighted house out of its stupor.

As the realities of Mrs Alistair's scheme come to the fore – including accusations of 'farming' her guests' babies to the highest bidder – the attention of the authorities looks finally to be roused. But is a bitter kind of justice when so much suffering has already come.

There is little to smile at in Jonathan Rigby's latest production, but its emotional force is undeniable.