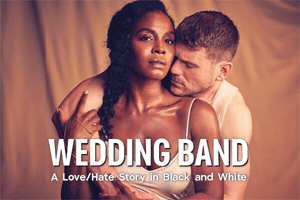

Wedding Band: A Love/Hate Story in Black and White at the Lyric Hammersmith Theatre – review

Monique Touko’s production runs until 29 June

Written in 1962, but not premiering until 1966 in Ann Arbor (it was a decade before it made it to New York), Alice Childress’ play Wedding Band was blistering in its portrayal of an interracial relationship in Carolina during the First World War. In its UK premiere, directed by Monique Touko, its fire and anguish is still mostly preserved. It’s almost epic, and finding a pace that suits its slow-burn first half and its frenetic second is tricky, but it’s not worth missing.

Julia (Deborah Ayorinde) arrives amongst her neighbours of mainly women and girls living in poverty but equilibrium, slightly withdrawn. She seems an anomaly, a seamstress with some money of her own, unmarried but in a ten-year relationship, still yearning: reading a letter to Mattie (a crisp and affecting Bethan Mary-James) from her husband, away fighting, she’s transported.

Julia’s been in mutual but impossible love with a white man for years. Her wedding band must go on a chain around her neck, while Herman (David Walmsley) wears one on his index finger. While he refuses to leave the bakery he owes to his mother, Julia dreams of escape for them both: Philadelphia or New York.

When Mattie and Lula learn the race of Julia’s longstanding boyfriend, they leave their arms, outstretched to God mid-prayer for her to be delivered into marriage, in a horrified, frozen state. The news couldn’t be much worse. Miscegenation laws in the South mean grim prospects if they’re seen together, potentially beyond the couple themselves.

Julia’s unreachable: her relationship has survived this long because both she and Herman have consciously made themselves so. It has its own toll. While she leads an itinerant life, moving and moving, Herman’s family push a woman he isn’t interested on him. The sacrifice isn’t exactly evenly spread. As Julia, Ayorinde is a luminous, romantic, increasingly desperate presence. It’s still welcome and rare to see a Black woman as the central, tragic figure: it’s her play, not Herman’s.

Fanny’s guesthouse is made up of wire fences and wood boards in Paul Wills’ design. The central point is Julia’s bed, around which everything dry and outside orbits. Shiloh Coke’s music finds the characters spirituals and blues, though largely we’re listening to the great torrent of dialogue. Childress’ style is both light and quippy, and grand: every character gets lines which sing. Nelson (an upright, charming Patrick Martins), Lula’s adopted son, fiercely clashes with Julia over Herman, and is gentle and slippery in turning down the advances of Fanny (a hilarious Lachele Carl), the enterprising landlady and self-appointed representative of her race.

Childress’ writing takes its time, running its fingers over the full texture of these characters’ lives, bickering over what’s proper, not without affection. The first act might seem at first blush sedately charming, even quaint, but horror is peering over the fence with a sweaty face. Julia has to stand her ground against a sour, leering whiteness in the form of a local salesman (Owen Whitelaw) even before the white folk really start turning up. Matt Haskins’ lighting leaks in an uneasy paleness as Herman ails in Julia’s bed, just as when the bell man threatens to rape her, the usual warmth outside, somewhere else entirely.

All sorts of sickness is discovered. Wedding Band is a pleasurable well-made play: it’s stuffed to the brim with the detail of these characters’ lives, and Childress’ consideration of how each is tied together by the lines of labour, gender, desire, prejudice. We know what keeps them where they are, and how they look at each other. Not for nothing does Fanny dismiss a contractor who won’t refund her as a “Black Jew”, or do Mattie’s girls (her daughter and the white girl she minds for money) play incessant games of “Indians” with each other.

Touko’s production sometimes pauses in these moments where haste would better serve, leading to an emphatic underscoring of Childress’ layers that isn’t really necessary. Touko ends with a glimpse of the future, the characters united, refreshed, in water; this, on the other hand, feels a little sudden, not really an aesthetic part which the production felt it was missing up to this point.

But we’d spend even longer with these characters if we could. The end comes all too abruptly, which is saying something for a play of two hours: while Julia careens from apparently mild breakdown to relative placidity, the community of women prepare to lose Nelson to war, perhaps for good. Herman and Julia’s relationship is undone, stripped back to its barest bones of love and hate (as the play’s subtitle implies): but it did happen.