Brian Friel’s Faith Healer is one of the great 20th century plays – and one of the Irish dramatist’s most frequently performed works. Its cast iron structure seems simple, yet it is far from straight-forward. Different productions tease different meanings out of its complex interplay of faith, doubt, and every shade of love and hope.

The first actor to play the fantastic Frank Hardy, the faith healer of the title, at its out of town premiere in Boston in 1979, was the treacle-voiced film star James Mason, who was then 70. Audiences didn’t quite know what to make of it all and at one point Friel was in such despair that he swore never to write another play. The legendary Irish actor Donal McCann took over the role when it was staged at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin in 1980 and reprised it in 1992 when I first saw it.

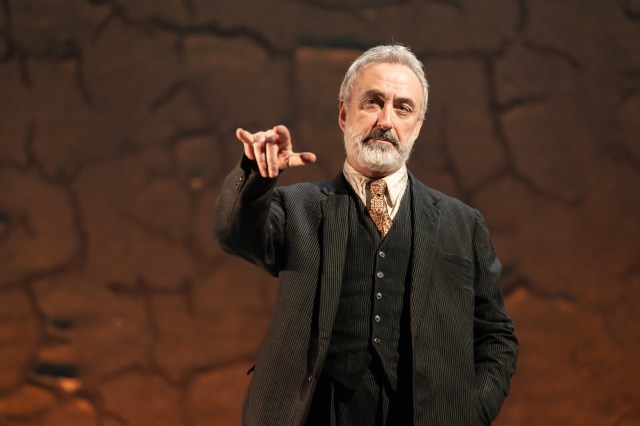

Now it has become a staple, and whoever stars and whoever directs, Faith Healer continues to yield revelations. This new production, directed by Rachel O’Riordan, stars Declan Conlon as Frank, Justine Mitchell as his long-suffering and agonised wife (or perhaps mistress) Grace and Nick Holder as Teddy, his Cockney tour manager whose ebullience conceals a profound sadness.

The approach is straight-forward. Colin Richmond’s set is dominated by a large banner advertising Frank’s miraculous events, and by a cracked wall that, thanks to Paul Keogan’s lighting, changes colour and texture as the evening and the story progress. It begins with Conlon’s laid-back Frank, hands casually in pockets, musing on the life he has led and, particularly, on two contrasting evenings: one when his gift allowed him to heal, and one when he knew “with cold certainty that nothing was going to happen”.

Mitchell’s Grace hunches in a chair when she recalls the same events and others that Frank has chosen not to remember, infinite longing in her eyes as she conjures a man she couldn’t bear to live with yet couldn’t be without. Holder’s Frank, opening beers, tugging down his tartan waistcoat, treats his monologue like a musical hall turn, pushing the words out into the air like exclamation marks as he recalls a whippet who played bagpipes as well as events on the road. Conlon then brings the show to its close, recalling once again a life scarred by alcohol, and questions that he cannot answer and cannot shut out.

Certain phrases repeat like incantations through the recitations. Long lists of the names of towns where the trio set up camp in places that are “relics of abandoned rituals”; the arrival at “a pub, it was a lounge bar really” near Ballybeg. But in other respects, memories are conflicting. Each of the trio blames someone else for the use of Fred Astaire’s recording of “The Way You Look Tonight” to accompany; none quite agree on the circumstances surrounding the tragedies that have led them to this point. Or indeed on small affairs, like whether Grace is a mistress or a wife, and whether it was raining or sunny when they reached a town called Kinlochbervie where something terrible happened.

The play is written both naturalistically and with the nuance and meaning of a poem. It lands in unexpected ways. O’Riordan opts to play up its humour and its social observations – the sense that this is describing a lost world of faith, of “hopeless hope”, as much as it is mapping the suffering of three individuals. The poetry is allowed to emerge quietly, landing its devastating blows, its uncomfortable truths.