The Oresteia (Shakespeare's Globe)

Adele Thomas’s ‘more traditional but no less powerful production’ impresses at the Globe

© Robert Day

As in an unreliable bus service, you wait ages for one to come along, then three come along together; so it is with Aeschylus's Oresteia this year, the fountainhead of our drama and the only surviving trilogy from Ancient Greece's 5th century BC golden age.

Just as Robert Icke's outrageous and powerfully elaborated modern dress version (complete with a brand new first play) transfers from the Almeida to the Trafalgar Studios, Adele Thomas's more traditional, no less powerful and hieratic production, in a faithful version by Rory Mullarkey, releases a more accurate idea of the trilogy's meaning and structure.

And there's still Blanche McIntyre's revival of the Ted Hughes translation to come at Home in Manchester next month… here, we start with the watchman on the tower seeing the flame coming home to the palace at Argos, where Katy Stephens's vengefully unforgiving Clytemnestra awaits the return of Agamemnon (George Irving) from Troy; ten years ago he sacrificed their daughter, Iphigenia, to the gods in exchange for a fair wind to the war.

The palace is covered in chipboard, flames burn in the standing bowls, the Chorus of seven elders – in dark suits and dresses, trilby hats, briefcase and laptop – mediate the dilemma with a terrible sense of foreboding, underpinned by the dirge-like music (on saxophone, horn and clarinet) of Mira Calix emanating from the gallery.

The first two plays – Agamemnon and Libation Bearers – end with an identical tableau of carnage of two pairs of lovers, the third, Eumenides, with the first murder trial in history, with a free vote for the jury and a tie-breaking decisive vote for the goddess Athena (Serbian actress Branka Katic in a glittering gold sheath).

The play reaches forward to us in the translation of the ferocious zombie-like Furies, who pursue Orestes (an increasingly impressive, helplessly tortured Joel MacCormack) to his destiny, into agents of civic order and civil obedience; superstition and the revenge cycle have been replaced with a modern equilibrium. But of course they haven't. The way the world is now we're right back there with Aeschylus and his audience.

For this venue is ideal for Greek tragedy, as we've seen with the Frank McGuinness version of Euripides's Helen five years ago. The language suits the skies, and in the prophetic tale of the ungrateful lion cub that kills and devours his human hosts, and in Clytemnestra's dream of the snake she suckles, you experience the vividness of the metaphors while feeling transported back in time.

And this is because Mullarkey, with the aid of classicist Lucy Jackson, has revisited the text line by line, speech by speech. The result may not have the reverberating muscle or knottiness of the Hughes or Tony Harrison translations, but it sounds exceptionally fine to me, with witty, appropriate anachronisms, hidden rhymes and declamatory fervour.

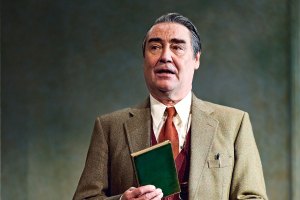

The Chorus, led by Brendan O'Hea and Paul Rider, is tremendous, there's a dervish-like witch of a Cassandra from Naana Agyei-Ampadu and a hilariously dissolute Aegisthus, Clytemnestra's lover, from Trevor Fox.

These plays are as much about hospitality, in the broadest sense, as they are about war, murder and revenge. That's why they never date and, in going towards Aeschylus, they come alive more immediately in the present.

The regular Globe company jig at the end is replaced with a short satyr play, the joyous ensemble spilling through the pit, bearing aloft a huge golden phallus. As Coral Browne said when a similar erection appeared on a plinth ("Plinth Philip or Plinth Charles?" enquired a bemused John Gielgud) in Peter Brook's version of Seneca's Oedipus at the Old Vic — "Well, it's no-one I recognise, dear."

The Oresteia runs at Shakespeare's Globe until 16 October.