”The Ocean at the End of the Lane” at the Lowry, Salford and on tour – review

© Brinkhoff/Mögenburg

The play’s central plot follows a boy, recovering from his mother’s death, who has to overcome a mystical parasite that tries to invade his family. Fly Davis’ set brilliantly conjures this fantasy forest setting, with dense knots of gnarly wood at the wings. Steven Hoggett incorporates it into the movement, with fingers splayed into twigs that snag clothing or brush faces. It’s also embodied by Finty Williams’ Old Mrs Hempstock, whose hair is plaited like twine. She captures the fey elderly wisdom and care of grandparents, her voice croaky but tender as she carries a staff like a mage.

The tangle of branches also resembles a child’s scribble. The play presents stories as an anaesthetic and the way death activates the imagination, the forest growth glowing with light like synapses in the brain. The boy re-reads books to access memories of bedtime stories with his mother. With her loss, he naturally falls into tales of fractures in reality and a “rip in forever”.

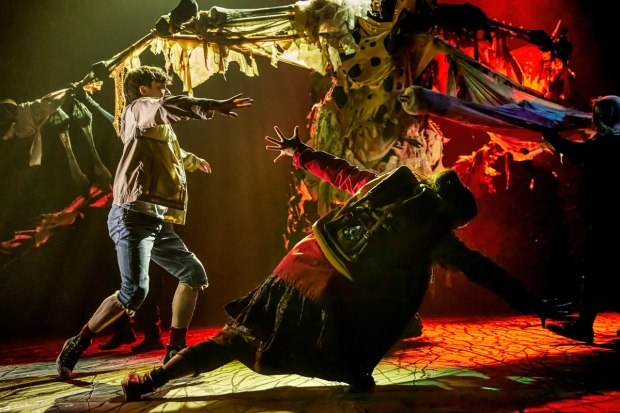

All the threats and danger are shot through with these ruptures and skews. A monster punctures a hole in his body and disorients him with self-replicating doors; children’s toys are used as bait for predatory birds that voraciously disembowel. Samuel Wyer designs them as ragged, ripped and torn puppets. The “hunger birds” are formed of tenebrous claws, beaks and shards; the “flea” of bones that jut out of sinewy membrane on a skeletal frame. They all emerge from a sinking black abyss at the back of the stage as deep as an ocean.

© Brinkhoff/Mögenburg

We see the same depths in the well of unspoken anguish that anchors down Trevor Fox’s Dad, carrying himself with a weight of grief – his pauses look like efforts to keep it buried so it doesn’t surface. His slow, tired voice also carries a disappointment about trying to be a better father than his own, contrasted against the whimpers and higher pitch of Keir Ogilvy as his sorrowing son. Millie Hikasa is endearingly coltish as his friend, Lettie, while Charlie Brooks’ sinister Ursula starts with unnatural sweetness – every tone honeyed and movement fluid – before turning it inside out into thorny menace.

The story’s lore isn’t as clear as it could be, suddenly introducing new concepts without the exposition to bind it all together or properly establish how this fantasy world intersects with the real one. There’s nothing quite as effective as the simple premise that a child’s propensity to dream and invent will wilfully interpret a duck pond as a magical ocean.

But its expansive spectacle ensures it translates across. There’s the subtlety of a man hoisting his younger self onto the stage to replay a memory, as well as the grandness of a pearly, rippling sheet sailing over the audience like a wash of seafoam. And, perhaps more affecting than any of it, is the sight of parents trying to find ways to reach in from the edges of their children’s lives and keep them safe.