Review: Written on Skin (Royal Opera House)

George Benjamin and Martin Crimp’s admired 2013 opera returns in Katie Mitchell’s production

© Stephen Cummiskey

This revival is an excuse to be dazzled once more by George Benjamin's pellucid score; but also, now that Written on Skin is on its way to becoming a repertory piece, to wonder why it works, and how effective it might be (or not) in a production other than Katie Mitchell's establishing vision.

The first point is easy to answer. It works because the music, a 90-minute coiled spring, seduces and grips, and also because Martin Crimp's libretto tells a vibrant tale by means of graceful epigrams and textual elegance. Of an agitated woman: "Eyelids scrape the pillow like an insect". Of the future: "Eight lanes of poured concrete".

It's enough to make one think that a different staging might illuminate Benjamin's manuscript rather better than Katie Mitchell's production. On second viewing Vicki Mortimer's split-stage designs, divided between the earthbound (utilitarian rustic) and the heavenly (neon strips and a pre-fab stairway to heaven) diffuse rather than concentrate the attention. Stage business in the modern section is loaded with Mitchell's slo-mo walks and onstage theatre-making, but it seems more self-indulgent this time round. And while the patina of ritual is apt for what Crimp himself calls "a hot story within a cool frame", it blanches the vitality of the music.

Written on Skin concerns an urbane tyrant, the ironically named Protector, whose self-aggrandisement prompts him to commission a vanity project from an itinerant creator of books, the mysterious Boy. Unfortunately the Protector's wife, Agnès, falls for their house guest and does the naughty with him, and it all ends badly over a hearty dish from the Andronicus cookbook.

'Grotesque transubstantiation'

It's easy to see why the opera will have appealed to Mitchell. She is no great fan of the male of the species, and a protagonist who declares of his wife that "her obedient body is my property" must have seemed ripe for retribution. That makes her restrained depiction of the ambiguous conclusion all the more commendable.

Benjamin's score, which he conducts himself, sustains its tautness over three short acts (no intervals, just a drop curtain and some coughing time) and makes use of an orchestra of all the talents: the standard instruments plus a bass viol and a prominent episode for glass harmonica. He tends to vouchsafe melodic passages to solo instruments. The composer's stated desire to be anti-romantic doesn't mean he's anti-dramatic, and febrile outbursts rupture the hypnotic mood at intense or shocking moments.

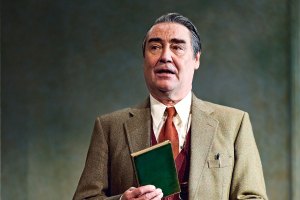

The five-strong cast includes several of the work's creators. Christopher Purves again sings the Protector, baleful yet mellifluous except in some cruel interpolations for the baritone's head voice, while Barbara Hannigan, recently Mitchell's Mélisande (and Pelléas et Mélisande was one of Benjamin's avowed influences when planning this opera), returns in triumph as the passionate, wilful Agnès. She interprets the grotesque climactic transubstantiation with devastating simplicity.

Mezzo Victoria Simmonds repeats her role as an Angel, joined on this occasion by no less a figure than tenor Mark Padmore as well as a handful of silent supernumeraries. All have been rigorously prepared for this revival by Mitchell and her admirable deputy, Dan Ayling.

However, it's Iestyn Davies who raises the production to new heights. The countertenor makes his ROH role debut as the Boy, with an enigmatic presence that renders the harmonic eroticism of his duets with Hannigan all the more intriguing. Indeed, his melismatic delivery of the word 'merciful' suggests that he's a celestial visitor to a rotten world, come to give base mankind a bit of a kicking. If so, we could do with him now.

There are further performances of Written on Skin on 18, 23, 27 and 30 January.