King Lear (Northern Broadsides – Tour)

Jonathan Miller’s production is agile, enjoyable and thoroughly interesting

© Nobby Clark

Jonathan Miller, 80 years old and not going quietly into that good night, has directed his favourite Shakespeare play eight times and now renews his partnership with Barrie Rutter's Northern Broadsides – they did a luminous revival of Githa Sowerby's Rutherford and Son two years ago – with this pellucid, quick and conversational take on the greatest tragedy.

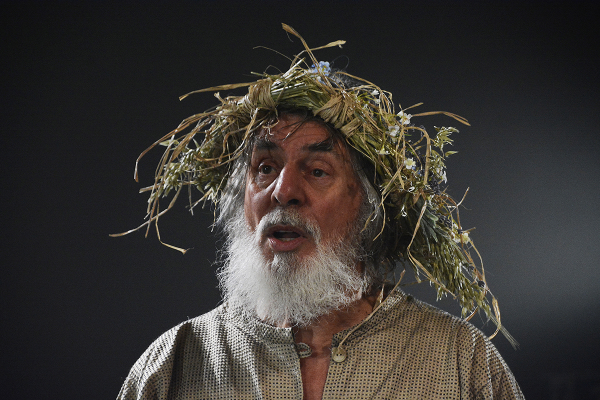

Rutter himself, now 68, plays the title role for the second time – he leapt into the breach fifteen years ago when Brian Glover, slated for the first Broadsides Lear, died, and exchanged Fool's motley for regal robes and rags – and has tempered his natural ebullience and vigour with a piercing study of someone losing their mind.

So, he's not dividing up the kingdom in a rage but testing Cordelia's devotion, intently watching her through her elder sisters' gruesome protestations. He does so in a mist of mischievous calculation which segues into a fog of Alzheimer's. There's no "howl, howl, howl" – Cordelia's corpse is carried in an improvised hammock by others – but a quiescent expiration, like a deflated balloon.

Rutter's leaning at this point against one of the two steel girders that Isabella Bywater cleverly incorporates into her minimal design of a chequered floor and Tudor furniture. The wonderfully atmospheric grey brick tunnel that leads off is where Gloucester is blinded – while Nicola Sanderson's sadistic Regan watches from centre stage, as Frances de la Tour did in a previous Miller production at the Old Vic – and where the trumpet challenge ominously sounds.

There's a price to pay for the cutting that brings us through in just under three hours. Fine Time Fontayne's Fool – a white-faced old familiar in a velvet red hat – is denied a chance to make sense of his more recherché jokes, and the hovel scenes, usually done so well by Miller, are over-skimped.

But after the unsubtly amplified blare of the Juliette Binoche Antigone at the Barbican, it's a delight and a relief to hear the springy, northern-accented vocals of the cast, Rutter's "Blow winds and crack yer cheeks," immediately propels the second half into the great scenes at Dover and the military encampment reunions. There's no posing or hanging around.

Andrew Vincent is a highly sympathetic, ever watchful Kent, for once properly disguised when banished so that not even a Lear in his perfect mind could recognise him, while John Branwell's fleshy and susceptible Gloucester is as tragic a victim of his sons' elaborate dislike of each other as is Lear of his daughters' bitchiness and rivalry.

This agile, enjoyable and thoroughly interesting production is in Hull this week, then touring south and north, from Bath and Cheltenham to Leeds, Scarborough and Liverpool through mid-June. It's more than well worth seeing, but I'm especially glad I saw it in Halifax.