Hamilton may have the most Olivier Awards nominations, but winning is no dead cert

Matt Trueman reflects on this year’s Olivier Award nominations

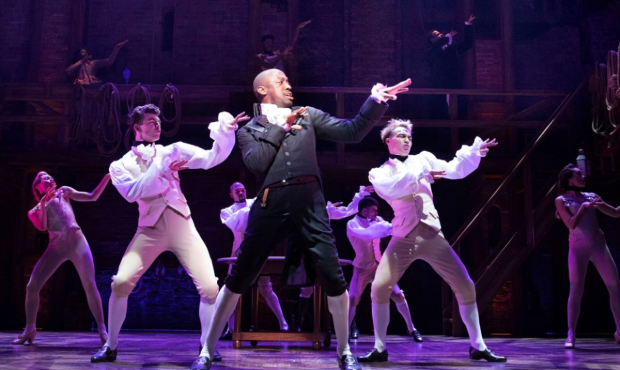

© Matthew Murphy

Hamilton was always going to grab the headlines. Thanks to its delayed dates, the result of that refurbishment over-running, the Oliviers were the first major British awards it was eligible for and – boom – did it deliver. A record-breaking haul of 13 nominations sees Lin-Manuel Miranda‘s hip-hop historical immediately leapfrog Harry Potter and the Cursed Child and Hairspray, both of which clocked up 11 in their time. It’ll take quite some beating. How many shows have enough fully-fledged complex characters to give six separate actors a shot at a prize? That, in itself, is a credit to its genius even before a single note's sung.

What’s more, you couldn’t complain about a single one of Hamilton's nods. If anyone gapes at three supporting actors, hit them with Michael Jibson’s scene-stealing King George, Jason Pennycooke’s peacocking Thomas Jefferson and Cleve September’s sweetness as Hamilton Junior. Two leading men? Come on: Giles Terera and Jamael Westman could happily walk home with a statuette each. Personally speaking, I wasn’t entirely convinced that Rachel John and co got the full measure of the Schuyler sisters, but such is the trickiness of Angelica’s role and her "Satisfied" rap, it would have been criminal to leave her off. As for the rest of the creative team, only David Korins’ ye-olde stained timber set went unrecognised and given the strength of British theatre design right now, that’s not exactly unfair. Everything else more than earned its accolade.

If I tripped into a bookies, I’d have Hamilton at five, maybe six max

But brace yourselves, Hamil-fans. It’ll win the day, yes, but Hamilton probably won’t top the charts. To do so, it would have to win nine of its 10 categories as Harry Potter managed last year, though only eight to beat Matilda to the best-faring musical. Either way, I’d hazard it’s going to hit stiff competition. Sure, Miranda might as well start penning his speech now, but his creative team colleagues can’t be so confident – not that they’ve much space left on their mantelpieces.

Unlike the Tonys, the Oliviers doesn’t split its directors by musicals and plays. That means Tommy Kail’s up against the very best of British: Sam Mendes, Rupert Goold, Marianne Elliott and, the odds-on favourite, Follies' Dominic Cooke. Likewise, choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler has the misfortune to land in the year of super-duper dance-theatre, head-to-head with 42nd Street's Randy Skinner and Christopher Wheeldon’s dazzling An American in Paris. No guarantees there, either. Follies's design team could pip Hamilton's too: Vicky Mortimer’s costumes and Paule Constable’s lights. If I tripped into a bookies, I’d have Hamilton at five, maybe six max.

Still, spare a thought for the new British musical. Everybody's Talking About Jamie and Girl from the North Country are rightly recognised across the board – the latter raising the intriguing possibility of Ciarán Hinds winning best actor in a musical without singing a note – but it’s a huge shame not to see two delightful off-beat tuners in the mix: Tim Philips and Marc Teitler’s gorgeous The Grinning Man and the heart burst that was Romantics Anonymous.

This is, almost certainly, the most ethnically diverse list of Olivier Award nominees ever

Organisers, meanwhile, owe Hamilton big time. Its dominance completely changes the story. This is, almost certainly, the most ethnically diverse list of nominees ever. Take Hamilton away and it’s a long way short: Sheila Atim and Audra McDonald are the only non-white nominees from everything else nominated, and we’ve got an all-male list of new plays.

The last seems a real shame in so strong a year. The National’s dominant Dorfman space has been cut out completely: nothing for Nina Raine‘s Consent, for Annie Baker’s John or Inua Ellams’ Barber Shop Chronicles, let alone David Eldridge’s delicate Beginning. All of them are far better – not to mention far newer – than Lee Hall’s clumsy adaptation of Network next door.

If a show can’t squeeze enough in, it’s never going to get a look-in

The two things, incidentally, aren’t at all unconnected. Since the Society of London Theatre changed the Olivier voting process – giving SOLT members a vote alongside its own independent judges – the awards have skewed in favour of big theatres and long runs. In short, SOLT has a lot of eligible voters and if a show can’t squeeze enough in, it’s never going to get a look in.

Hence the exclusion of the National’s smallest, but also standard runs at the Royal Court, Young Vic and Almeida. No Albion, no Carey Mulligan in Girls and Boys, nothing for The Jungle. It’s why those quirkier, oddball British musicals aren’t on the list either. The Grinning Man‘s played to 380 a night at the Trafalgar, while Romantics Anonymous sold out to 340.

Meanwhile, every show nominated in a theatre category played to a capacity twice that size or more. The one curious exception was Witness for the Prosecution in a bespoke 360-seat space, though that has been running for five months and continues with an open-ended run, while Ink's Duke of York’s run held 640 a night – again, for months on end.

You see the problem? In privileging big spaces, the Oliviers exacerbate every structural hierarchy that already exists in the industry. It privileges those artists that are already privileged. SOLT shifted its voting process to level the playing field between commercial producers and subsidized theatres. Until it tweaks it again, it will struggle to make room for proper diversity. A Hamilton only comes along once a generation. That’s not enough.