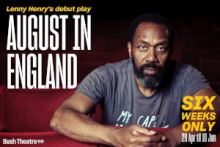

”August in England” starring Lenny Henry at the Bush Theatre – review

© Tristram Kenton

Campaigner, actor, comedian and knight of the realm Lenny Henry has written this monologue to illustrate the inhumanity of what happened and to highlight the impact it has had on the very ordinary lives of those of West Indian heritage that were so horribly blindsided by the whole scandal.

It is also Henry that takes the performance reins as August Henderson, the son of Jamaican parents that moved from Jamaica to Peckham in the ’60s. Jamaica was an English colony at that time and part of the British Empire. Free movement within the Empire meant that this was a perfectly acceptable move and indeed was often actively encouraged by the British Government. August was just eight when he arrived on our chilly shores. With Peckham proving to be too rough, it was the Midlands that beckoned, and the West Indies become West Bromwich – familiar territory for Henry.

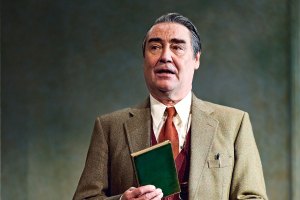

August retells his whole life story, moving around his comfortable front room, referring to the family pictures on the wall as he talks about his parents, romances and the raising of his children. He ponders on grief as the machinations of life lead him into periods of depression and loss as well as happiness and success.

Henry’s comedy roots are obvious to see as he laughs and jokes his way through the storytelling. He casually interacts with the crowd and happily acknowledges the ample support being verbalised by the engaged audience. It often feels a little too much like a stand-up routine, however, and the dramatic takes a back seat far too often. The vast majority of the 90 minutes (no interval) is spent looking back at August’s life. It paints a vivid picture of the man, kind-hearted but flawed, aspirational yet content. But it leaves little time to fully examine the effects of the trauma that unfolds following the arrival of a letter threatening deportation.

There is only a nod given to the social context: August refers to his upbringing and his education, and there is brief mention of the bad old days of the 70s and the presence of the National Front and Keep Britain White groups. But otherwise, Henry stays surprisingly clear of too much political or social commentary and prefers to keep things pretty domestic instead.

© Tristram Kenton

In the final scene, a brutal jolt takes us from the comfort of August’s front room setting to a cold and austere detention centre. It evokes the chill and brutality of the situation adeptly. CCTV cameras that project live images onto the back wall give a dystopian feel to the inhumane process that is occurring.

It’s a story that needs to be told and its impact understood much more widely. At the end, a collection of projected interviews with real people that have been affected is a stark reminder of the damage done. Whilst Henry’s words may at times lack subtlety and may not always reach the emotional depths necessary, the testimonies from the real victims speak volumes, even if it does come as another jolting change of pace.