A Voyage Round My Father on tour – review

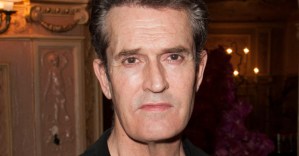

Rupert Everett stars in John Mortimer’s celebrated autobiographical play

John Mortimer’s A Voyage Round My Father has always attracted big-name actors into the role of the cantankerous patriarch, from originator Alec Guinness to Laurence Olivier on celluloid and, more recently, Derek Jacobi – a who’s who of great thesps who have seen something in the project to sign up. It is an old-fashioned star part, and Rupert Everett, who steps into the role in this Theatre Royal Bath production, relishes every moment of ‘showing’ a great performance. Whether you believe a whiff is another matter, in a production of this 1970 play that makes it feel even more old-fashioned than that.

Richard Eyre’s handsomely mounted production is well done for the most part, but it’s created for an audience who wants to bask in the bucolic mid-20th-century vibes of respectable Middle England. The question about why this play, why now, is never answered and there is no sense of urgency as a result.

Mortimer’s autobiographical piece about the relationship between himself and his father traces a line in how our parents shape us, Jack Bardoe’s Son casts an unsentimental but loving eye over his journey into adulthood as he comes to understand the world as shaped by his father. Originally seen falling off a ladder that blinds him, Everett’s dad is a merciless, first-class mind, unwilling to give advice other than to avoid being heroic in war or saying the word ‘Rats’ to stop the tear ducts opening.

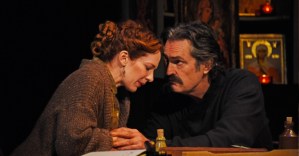

Over the course of the story, we see Bardoe find his own love for this difficult but brilliant man while trying to find a way to connect, mostly unsuccessfully. Chronologically, we head through 30-odd years of memories from Mortimer junior’s boarding school years as a euphemistic headteacher talks pre-pubescent boys into taking cold baths to ignore their unconsidered carnal desires, to sapphic literary trysts that take place away from the seeing eyes of the villagers, film set hi-jinx on patriotic tat and then into domestic drudgery as he gives up on a writing career for a place at the bar.

Bardoe effectively portrays the first four stages of Shakespeare’s ages of man (infancy, schoolboy, teenager, and young adult) but it is Everett who takes over from ‘the justice’ onwards who dominates the night. There has always been something performative about him, and as he enters his more mature dotage, he is playing beyond his age, as in rebellion of his Dorian-like years.

From the first time we see him, his grimace-marked face is stretched downwards as if to suggest years of ignoring delight, his manner slow and drawn out, already stripped of bon-vivant. It is only in the courtroom when he skillfully destroys case after case do we really get a sense of the purpose and spring of this man. By starting from defeat, the performance just becomes more and more a range of old man tics. The acting is never far from the surface.

It is Allegra Marland as the daughter-in-law who challenges the paternal dominance of the household and makes the strongest impression. The energetic flirtations of the first meeting develop into frustrated long-term loneliness as she realises she doesn’t really understand the man she fell in love with.

Eyre’s production is customarily thoughtful and full of detailed cameos, not least Julian Wadham’s pompous headteacher, and John Crowley’s design shows off the arboreal wonder palace that Mortimer senior created. Yet ultimately, it’s a very old-fashioned evening decked with a sprinkling of star quality but not landing it wisely.