Morgen und Abend (Royal Opera House)

The Royal Opera stages a new work about birth and death that is bold, original and affecting

© Clive Barda

The great mysteries of life are its beginning and its end. Most of us, if we’re lucky, can cope with what happens in between, but the two extremities are beyond our control and comprehension. This helplessness touches primal human feelings, so an opera that addresses the hatch and dispatch of existence has a head start in squeezing our emotions.

Operas frequently deal with death (although rarely with birth) but their themes are usually more earthly. Typically they address the revenge or heartbreak of the living. Morgen und Abend is different because it’s about being dead.

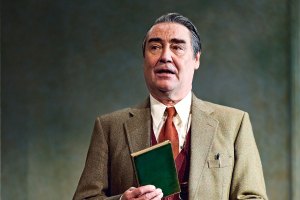

First, though, it must give birth. The libretto by Jon Fosse, based on his own novel, opens with a fisherman, Olai, waiting for his new son to be born. He will be named Johannes. The composer Georg Friedrich Haas sets Olai as a speaking role, and in Graham Vick‘s dreamscape production he’s grippingly portrayed by the great Austrian actor Klaus Maria Brandauer, chairbound to emphasise the interior nature of his soliloquy.

It takes him 40 minutes to put it across. Babies have been delivered more quickly. But Haas is no common composer and his music needs to be approached with open ears. Nobody in Morgen und Abend actually sings until the opera is more than a third over, apart from a wordless offstage chorus. Instead, Haas interlaces Olai’s text with a musical language he himself describes as based on the perception of sound rather than anything more tangible.

'Distant oblivion'

If that sounds forbidding, it isn’t. Under Michael Boder‘s baton, antiphonal bass drums thwack to herald the slowly expanding string figures that serve as an aural hammock for the unfolding monodrama. The composer’s celebrated ‘microtones’ are no more dense than the average film score, their lineage from antecedents like Ligeti perfectly clear. It goes on too long, that’s all. When, 20 minutes in, Olai shouts "If only something would happen", one is tempted to agree.

The transition from Morgen to Abend – morning to evening; birth to death – is magical and sumptuous, one major chord swooping atonally into another, then on again, as the years of Johannes pass. Once he’s dead, though, the music develops a generic ghostliness that is progressively less original.

Johannes has a post-life journey not unlike that of Gerontius in Elgar’s oratorio, except that his culminates not in the sight of God but in a distant oblivion.

Vick and his designer, Richard Hudson, have opted for a stripped back environment of white objects against light grey costumes and backdrop, with an ultra-slow stage revolve that allows memories to recede through altered perspectives while other relics take their place.

Baritone Christoph Pohl is exceptionally concentrated and convincing as the late Johannes, a man who sees dead people all the time in the form of his wife, Erna (Helena Rasker) and his lifelong friend Peter (Will Hartmann). The key character, though, is his living daughter Signe, a role sung with great poise and humanity by Sarah Wegener.

Morgen und Abend is powerful and moving in an oppressive, insidious way, and it’s well worth 90 minutes of your open-minded time, especially at the Royal Opera’s special bargain rates. But it has flaws and frustrations. The jarring leap from spoken English to sung German seems unnecessary; Erna come across as a cousin of Britten’s Miss Jessel (I half expected her to sing ‘Alas! Alas!’) and, as hinted above, the Morgen section gets in the way of a good ghost story. But if you are susceptible to Haas’s musical language it will creep under your skin as it did mine. I confess that when Brandauer missed his curtain call, for a moment I feared the worst.

There will be further performances of Morgen und Abend on 17, 21, 25 and 28 November.