For a Palestinian at Camden People’s Theatre – review

In the first couple of rows at For A Palestinian, you might catch the slight scent of oranges. It’s a painting featuring oranges which draws Wa’el Zuaiter to its artist, Janet, in Rome in the 1960s. Oranges remind him of the sea, he tells her: the sea of his home, of Palestine.

If Wa’el Zuaiter’s known to the audience at all, it’s for being the first assassination in Israel’s Operation Wrath of God, in response to the Munich Massacre in 1972, rather than for his hopes of translating the One Thousand and One Nights. It’s this Wa’el, a poet and lover of art opposed to harming anything, who’s the subject of this play.

The Mossad files on Zuaiter linking him to the terrorist group Black September have never been released: it’s presented as fact in Steven Spielberg’s Munich (2005), written by Tony Kushner, while two years after that, Emily Jacir’s art installation Material for a film which memorialises him was awarded the Venice Biennale’s Golden Lion. Many remain resolute that his death was a mistake.

This dispute isn’t the subject of For A Palestinian. Performer Bilal Hasna and director Aaron Kilercioglu named their play after the book of essays, published by Wa’el Zuaiter’s partner Janet Venn-Brown, after his death. Accordingly, the play is for and about the man himself, and about love: primarily, the dramatised relationship between Janet and Wa’el in Rome, and Wa’el and Hasna’s own longing for a homeland changed, and out of reach.

Hasna has the physicality of an animated film, all on his own: larger than life, the characters seem to step on each others’ toes ceding the space to one other, as he flows between accents, ages and body types. He has broad fun with the national stereotypes of Wa’el’s European friends at his pensione and his wizened old landlady Mariuccia, in an closed-eye grimace. He gives you goosebumps just by hugging himself.

Rarely, Hasna stills, and we hear recordings of him with his dad, with a tracked down friend of Wa’el’s, or other members of the team, discussing Wa’el or making the play itself. A calm, sad, and sometimes mischievous score by Holly Khan accompanies him throughout, its moments of harp and flute most memorable.

Hasna’s own background, as a young Palestinian of the diaspora who has never lived there, is an enlivening strand of the play running alongside, coming to the forefront at its close: he’s eager to find similarities between himself and Zuaiter, and notes the deferential treatment he and his family receive travelling to Palestine for a family wedding. The writing is compassionate and forceful throughout, though its end is perhaps slightly extended and over-emphatic. We understand so clearly where Hasna and Kilercioglu are coming from already.

The set design by Jida Akil is like an abstracted sketch of Wa’el’s story – piles and mobiles of orange slices, an orange frame, blue fabric – and contains little secrets. Ros Chase’s lighting is a masterclass in how to light a small space, utterly responsive and choosing colours wisely from a wide palette, not just orange. When she drains that colour away for what feels like the first time, as the Palestine cause loses public sympathy in Italy at the Munich Massacre, the black walls of the Camden People’s Theatre reassert themselves around Hasna hopelessly.

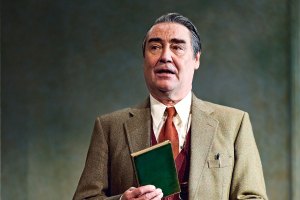

Hasna and Kilercioglu don’t let it end there in that darkness, pulling Wa’el and Hasna’s threads together to make a stab at hope for the future, partially through the telling this story. Clutching the book with the voices of those who made the show around him, Hasna barely seems alone onstage at all.