Review: An Inspector Calls (Playhouse Theatre)

Stephen Daldry’s production returns to the West End to mark its 25th anniversary since opening at the National Theatre

Before he was the director of The Crown, the glossiest and most addictive series currently on Netflix, even before he brought Billy Elliot to the stage, Stephen Daldry was a trail-blazing young thing, a re-imaginer of classics, an iconoclastic re-envisioner of theatre in a brave new image.

His version of An Inspector Calls, first seen at the National Theatre in 1992, is a superb example of his ability to haul an old warhorse out of the theatrical lumber room and make it seem bold, relevant and utterly thrilling. Even at this distance, the way he makes JB Priestley‘s socialist call to arms (written in 1945 and set in 1912) sing to the needs of today seems dazzling.

The production succeeds by turning a naturalistic drama into a theatrical box of tricks. It opens with children emerging from the auditorium to play in a theatre. As they raise the curtain, there is a beautiful yet disconcerting dislocation; Ian MacNeil’s crazily angled set has the floor of a bomb site, and the logic of the playroom, with swaying lampposts vanishing into an impossible perspective, and in the centre a doll’s house on stilts, too small for its adult inhabitants, gleaming in the dark.

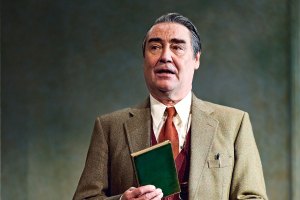

Crammed inside its shiny interior are the Birling family, rich and complacent. Outside looking in are the mysterious Inspector Goole (Liam Brennan) and a raggle-taggle army of children and dispossessed bystanders, looking on gravely as the Inspector reveals the family’s complicity in the terrible death of Eva Smith, an innocent girl punished for being brave and beautiful by a world that values the wrong things.

The production infuses his inquisition with a deliberate air of strangeness. Rick Fisher’s smoke-filled lighting, Stephen Warbeck’s melancholy music and Sebastian Frost’s sound design all add to the unsettling atmosphere; Daldry’s direction distorts eyelines, breaks the fourth wall, brings down the curtain in the middle of the action. The audience is as complicit in the Inspector’s investigation as the Birling family. It is our values that are also under scrutiny.

The play speaks so strongly because, at root, it is a powerful plea for compassion. It demands a recognition of the rights of the poor and the struggling and asks us to see ourselves as a community. Otherwise, suggests Priestley – in an image made utterly explicit on stage in front of you – fire and blood and anguish will follow. That message seems as relevant in a world that has just elected Donald Trump as US President as ever it did in 1945, or even 1992.

This revival has its rough edges. The performances are currently not as finely calibrated as the direction, though Clive Francis and Barbara Marten as the older Birlings are both impressive in their callous self-regard, and Carmela Corbett handles daughter Sheila’s journey towards tolerance and kindness with some conviction. The famous coup de theatre which sends the house crashing to the ground is not as smoothly or affectingly realised as it once was.

Nevertheless, it grips and holds. It was fascinating to see an audience full of school children studying the text for GCSE gradually lean forwards as the play exerted its powerful grip – and the production made something all too easily dismissed as dusty, come to vital and argumentative life.

An Inspector Calls runs at the Playhouse Theatre until 4 February 2017.