Review: Amadeus (Olivier, National Theatre)

Michael Longhurst revives Peter Shaffer’s play about the young prodigy Mozart

What a homecoming this is. Four months after his death, Peter Shaffer’s operatic epic returns to the stage on which it started – and in some style too. With a 20-piece orchestra swanning through the action, Michael Longhurst‘s ravishing staging makes a spectacle of Mozart’s music and, whether or not it eclipses Peter Hall‘s original (who knows and who cares), it yanks a masterful play into the present – a new generation let loose on a timeless classic.

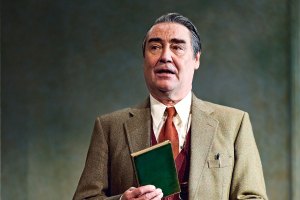

It’s a real crowd-pleaser, Shaffer’s play: a masterpiece that makes up its own rules. Shaffer sets up a bitter rivalry between the two musical megastars of classical Vienna: court favourite Antonio Salieri (Lucian Msamati) and the tyro genius Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Adam Gillen).

Both are fillet steak roles. Salieri, looking back on his life from his wheelchair, is the smiling schemester, eaten up by envy; "the patron saint of mediocrity" who destroys a greater creator than he could ever be. Mozart is the young upstart – not the poised genius of portraiture, but a brash, giggling, foul-mouthed superbrat. He’s a startling figure. As Margaret Thatcher insisted backstage first time around, "Mozart was not like that."

Well, he was – and boy does Gillen have fun with him. Dressed in candyish finery, with cotton wool hair and baby-pink DMs, he’s a chimpanzee tearing through court. Gillen cuts shapes like Freddie Mercury, then stands slack-jawed and gawping, waving limp lobotomised waves. Imagine Justin Bieber in a frock-coat; Johnny Rotten in britches.

Salieri is his opposite – a Viennese twirl with a sweet-tooth and absolute poise. Msamati glides him to a gilted existence, richer and richer while consigning Mozart to poverty. Salieri connives, Iago-like, to rob him of students and patrons, until life wears him down; a beautiful thing broken out of spite. Gillen seems to seize up, wracked with old age in only his thirties. Overhead, designer Chloe Lamford has a cherub weighed down with tassles, as if caught in a hunter’s net.

Shaffer’s play is a treatise on art’s place in the world – and, for all we relish the rivalry, it’s that wisdom which elevates it. Not only does it catch the tension between transcendent beauty and art’s practical purposes, it sees, in Mozart, the ugliness of genius: its arrogance, its queerness, its offensiveness to old ears and established norms. Their voices almost say it all. Msamati’s is gorgeous, a voice that cuts through the air, sharp and coppery, while Gillen’s grates. It is a shrill hee-haw, jarring on the ear.

Staged with the same restrained opulence he brought to Carmen Disruption – miniature glitterdrops and golden lighting – Longhurst’s production handles all of that richly. Lamford’s design, which has Salieri peering round curtains like an outsider, teases out the theatricality of fashionable Vienna; an age of appearances, like our own, and artifice. Bathed in Jon Clark’s lush lighting, this is a staging that basks in its beauty, even as it runs amok. Imogen Knight turns the orchestra into a dark, twitchy chorus.

At times, it is literally breathtaking. Its visual beauty holds you in suspense, then the music cuts through and the world seems to stop: the trills of The Magic Flute, the basso boom of Don Giovanni. Part of the play’s brilliance is in letting us into the music: Salieri's descriptions are like little tutorials, deconstructing the music to let us listen like experts. Brilliantly, Longhurst and musical director Simon Slater restore the radicalism of Mozart’s music. A bass drum beat bolsters one symphony, the cast bleating its melody like a football chant. Stood on his piano stool, Gillen’s Mozart conducts his orchestra like Calvin Harris revving up a crowd of clubbers. This was the end of the classical era, and Mozart made new things possible. He pushed music to the max; so beautiful it seems to hurt; exquisite as an orgasm.

Amadeus is currently booking at the National Theatre until 26 January 2017, with further dates to be announced. There will be a National Theatre Live broadcast 2 February 2017.