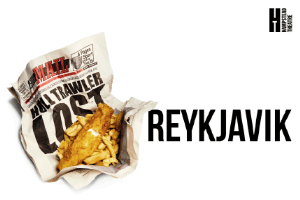

Hull-born Richard Bean’s latest play, the 1976-set Reykjavik, is a “spiritual cousin” of sorts to his 2003 work Under the Whaleback, which followed the deckhands on a fishing trawler. Having “failed to bring down capitalism” with this work, Bean has chosen the big boss as his central figure in this new piece. It’s very much a play of two halves: the first is set in head office in Hull and the second in the Icelandic capital, with a significant tonal shift after the interval.

Wealthy fleet owner Donald Claxton (John Hollingworth, effectively disillusioned and sleazy) is a Cambridge English Literature graduate (all his trawlers are named after canonical authors) who inherited the business from his father, a man who continues to live and breathe fishing. However, Donald has never actually been a seaman himself. The first ship under his watch (the Henry Fielding) has been lost, with many men drowned. None of them can swim – it only prolongs the agony if the worst comes to pass.

Claxton is preparing for the tradition of the ‘widows walk’, in which he visits every family on foot and is proffered innumerable cups of tea (don’t ask to use the bathroom of a woman you’ve made a widow, his father counsels, reeling off a list of alternative facilities). It’s the heart of the play which we don’t see but can certainly imagine.

Directed by Emily Burns (who previously helmed Bean’s Jack Absolute Flies Again and whose production of Dodie Smith’s Dear Octopus at the National was my favourite show of the year), the first half is a tautly written study of capitalism and morality (a bit Bernard Shaw-esque) and the second feels like a homage to Conor McPherson’s The Weir, in which the survivors tell ghost stories, few of which are particularly scary or gripping. What’s most engaging is the concept of fishing as something that’s imbued with a primal glamour; the men who come back with a successful haul like rock stars for a few days before they’re off again. It’s all an illusion, really, as the traditional funeral hymn makes their sacrifice sound noble and patriotic, when in fact the drowned men really “gave their lives for half of someone’s fish and chips supper.”

Bean has never been great at writing female characters and the women here are particularly ill-served. Sophie Cox has little to work with as the gormless young secretary Charlotte and overburdened hotel manager Einhildur. Laura Elsworthy is an assertive presence as Lizzie Jopling, a fishwife and club singer who hates her husband and wishes he had been one of the ones lost at sea but leaves the office tacitly agreeing to embark on an affair with Claxton (this isn’t mentioned again in act two and it feels implausible that she’d confide in him).

The stock characters of the second half largely represent the British abroad behaving rowdily (with greater license than most due to PTSD). Paul Hickey is striking as Claxton Sr and the Irish-Manx seasoned seadog Quayle and Matthew Durkan doubles as the jeans and woolly scarf-wearing vicar in the first half and Lizzie’s husband Jack, the troublemaker of the group. Adam Hugill is the innocent Snacker who clumsily flirts with Einhildur, while Matt Sutton plays the monosyllabic Baggie.

Anna Reid provides two effective sets: the dimly lit, old-fashioned office and the brown-and-orange Icelandic hotel. This isn’t one of Bean’s finest efforts but it is watchable – it’s mostly a shame that the potential of act one isn’t followed through.