Review: The Funeral Director (Southwark Playhouse)

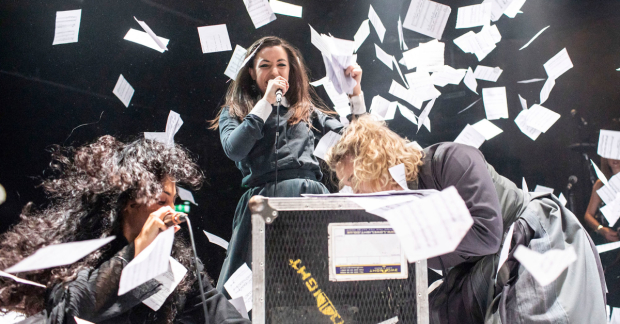

© The Other Richard

When you're surrounded by death all the time, how do you make time to celebrate life? These are underlying problems that haunt the Muslim couple who run a funeral parlour in Iman Qureshi's new play.

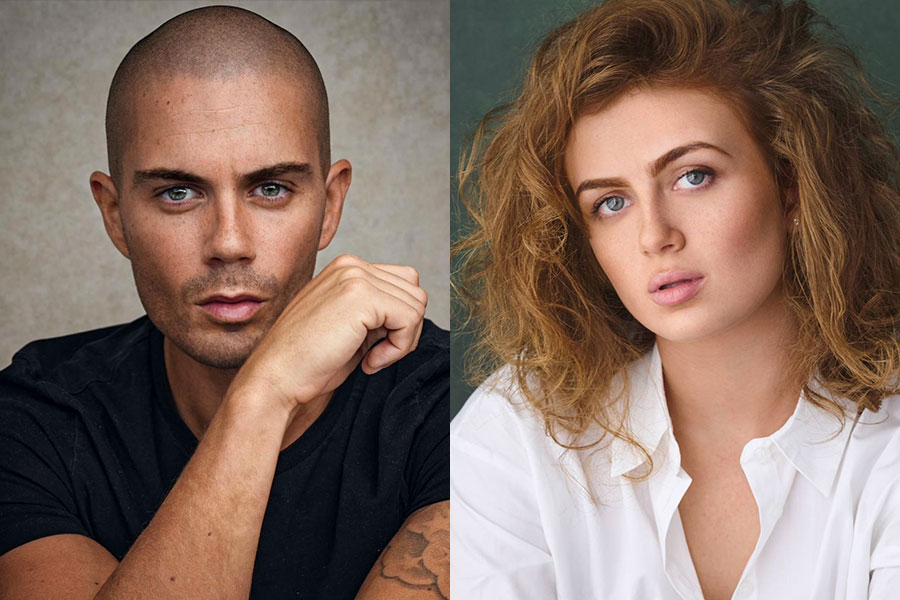

Still, all these problems seem to be under wraps – that is, until a white man comes to the parlour in the hopes of organising his Muslim boyfriend's funeral. Ayesha (Aryana Ramkhalawon) and Zeyd's (Maanuv Thiara) refusal to bury the man's boyfriend, on the grounds of his sexuality alone, has profound consequences which shake their community, threaten their livelihood and force them to confront their own marital issues.

The Funeral Director places life and death side by side. And the set design by Amy Jane Cook highlights this beautifully. One half of the stage is occupied with a welcome room in the funeral parlour – a sofa with patterned cushions, passages from the Quran on the walls, potted flowers and framed photos of Ayesha and Zeyd. The other half of the stage is in stark contrast to this, housing the room in which they work: a gurney, a sink, kafans (shrouds which wrap dead bodies), with some clinical white lighting (lit by Jack Weir) to go with it. Before the play is underway, the set alone suggests the thin line between not only life and death, but between outward appearance and grim reality. And, as the play unfolds, between long buried secrets and accepted cultural practice.

Tom Morley is phenomenal in his role as Tom, the grieving partner who knows little about Muslim burial traditions but simply wants to do right by his partner. His pain rings so true that his scenes become difficult to watch, making it that much harder to understand how Zeyd and Ayesha could turn him away. This is a play in which everyone makes bad decisions, and everyone must suffer the consequences. Even Janey (Jessica Clark), a human rights lawyer and old school friend of Ayesha's, is forced to unearth old mistakes.

Ultimately though, there isn't a strong enough sense of the community in which they live. And as difficult as this may be to achieve with a cast of four, the production would have benefitted from making the cultural pressures more tangible.

The play grapples with questions surrounding human rights. When Zeyd is accused of breaking the law for refusing to conduct a burial for a gay Muslim, Zeyd replies heatedly, "It's their law, not ours. Our law is Allah's law," and argues for his right to say no according to his religious beliefs. His speeches about feeling like a foreigner in Britain, about the media's insistence on consistently reporting about 'integration into British society' demonstrate just how complex his position is. On one hand, he is the victim of a society which will never accept him anyway; on the other, as Janey points out, his freedom of religion only extends so far as they do not infringe on another's human rights. Qureshi successfully delivers a complex narrative that goes far beyond simply presenting moral codes but cuts to the heart of what it means to live in between two, often conflicting, cultures.

However, it's a play which is too heavy. Despite excellent performances from all the cast, the show becomes too much to take in. With no interval and with almost every scene either a heart wrenching confession, or filled with frustration and rage, it becomes difficult to connect to the story.