G, directed by Monique Touko, is both a simple story told well and a multi-layered social commentary that will have audiences talking and debating all the way home.

A Candyman folktale, Baitface was once a teenager who was wrongly accused of a crime and in a panicked run from the police, was fatally hit by a car. Ever since he’s been haunting his old London borough, looking for the real perpetrator to seek his revenge.

Kai, Khaleem and Joy know that you don’t dishonour Baitface. You don’t walk directly under his pristine white shoes hanging from a phone line, and you show your respect in their presence by gently touching them before going about your business.

But Khaleem wants to show off to his new girlfriend, and in a moment of madness, he takes the shoes down to show her. In no time, the police have found his homework diary near the scene of a crime, and somehow neither Khaleem nor his friends can account for their whereabouts on ‘The Night In Question’. Baitface is coming for them.

The play alternates between the characters’ real world and a liminal space in which they are stuck in a few beats of CCTV footage, played over and over. Beautifully choreographed by Kloé Dean, the movements are stiflingly repetitive, and you can feel the tension between the characters’ desire to be anywhere else and their inability to leave. I’m not sure I would have understood what was happening here had I not had a quick flick through the script before lights out. CCTV footage is repeatedly projected on to the stage so as to explain the scenes, but the video isn’t always clear from the audience’s vantage point.

The three leads, Kadiesha Belgrave, Ebenezer Gyau and Selorm Adonu all embody the swaggering London teenager, easily brought to tears by a detention slip. They’ve got great chemistry, and despite all being fully grown adults, it doesn’t feel cringy that they’re playing children.

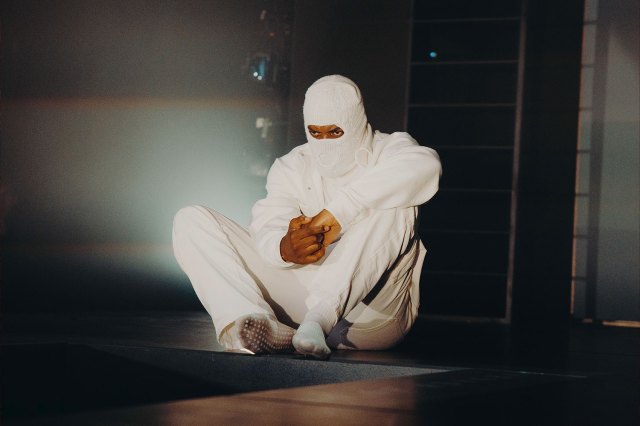

Dani Harris-Walters’ portrayal of Baitface is its own type of poetry. Besides one segment with narration, he has no voice, expressing himself entirely through awkward uncanny movement. He even manages to occasionally get a laugh without discrediting the seriousness of his character’s doomed fate.

Tife Kusoro’s writing is deceptively simple: on one hand, this is a classic comic supernatural thriller with quippy, honest dialogue. On the other it’s a social commentary on racial injustice and personal identity with moments of sobering, singing prose. Often when these genres combine, as with Nia DaCosta’s 2021 Candyman remake, the weight of the latter is too much for the former to bear; it asks too much of the silly premise to carry such a weighty political message.

In this case though, Kusoro deftly cradles both simultaneously. The audience is never choking on their laughter, never betrayed by their enjoyment on discovering that the play was more serious than they realised. Even in the big reveal, when all should be crushingly serious, the audience is allowed a laugh or two, which somehow doesn’t detract from the story’s message.