Review: Allelujah! (Bridge Theatre)

© Manuel Harlan

There are certain baseline expectations of a new play from Alan Bennett that mean he never disappoints. There will be some well-crafted jokes, often involving Yorkshire towns. There will be a sharp-eyed delineation of Englishness in all its eccentric variety. And there will also be some provocative political thinking, a sense that there are values worth clinging to that are in danger of being lost.

All are present and correct in Allelujah!, his tenth stage collaboration with the director Nicholas Hytner. But what's also notable is the play's good heart; it has a generosity and a passion that made me forgive it its occasional oddities.

It is set in the geriatric ward of the Bethlehem Hospital, an old-fashioned cradle-to-grave institution, where "both ends of life are catered for". It is, naturally, fighting closure because it is the kind of place that upwardly aspiring ministerial adviser Colin (Samuel Barnett) loathes to the bottom of his NHS reforming soul. The notion of a community hospital is, he opines, sentimental. "The State should not be seen to work," he says. "If it is seen to work, we shall never be rid of it."

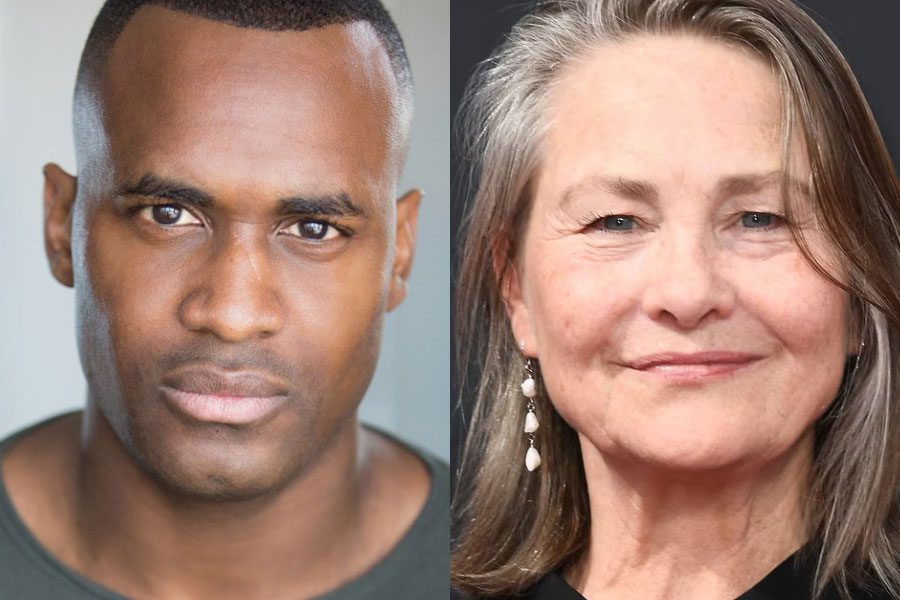

That savage observation, made when Colin comes to see his ex-miner father Joe (Jeff Rawle) who has been admitted to the geriatric ward for an infection, is part of the theme and an ingredient of the plot. Other strands include the way that families forsake their elderly relatives and a doctor called Valentine, who loves old people, but whose immigration status is suspect. Then there is Nurse Gilchrist (Deborah Findlay) who is determined to run a "dry" ward of continent patients, whatever the cost – and the dark plan she comes up with to relieve the bed-blocking crisis. Oh, and there's a documentary camera crew from local TV filming it all.

© Manuel Harlan

This is a clever device, since it allows the characters – all 25 of them – to speak directly of their inner thoughts or their past lives. And the assembled cast of older actors seize the opportunities given them with glee – particularly Gwen Taylor as the high-spirited Lucille ("I live the high life. Many's the knicker I've had to retrieve from the chandelier in that house"), Simon Williams as wistful Ambrose and Julia Foster as shy Mary. They also dance, in fantasy sequences beautifully choreographed by Arlene Phillips which reveal the liveliness concealed by their infirmity. And they sing, the anthems of the north and the songs of their youth, arranged by another long-time Bennett collaborator George Fenton, forming a choir because the young nurse on the ward (Nicola Hughes) thinks it is good that they have hope.

There is arguably too much going on for any character to emerge fully-drawn, and some of their characteristics are disappointingly caricatured, but Hytner keeps everything going with ease and aplomb. And Bob Crowley's simple set, with sliding panels recreating the wards, and a faux Monet Water Lilies above the grimly institutional walls, is immediately recognisable to anyone who has spent even an hour as a hospital visitor.

Bennett's craft as a writer, the way he slides effortlessly from the comic group scene to the single, telling moment is always apparent. Two stunning scenes could only have been written by him. In the first, Lucille and Mavis (lovely Patricia England) reminisce about the joys and disappointments of marriage, ending with the dying fall of "still it was better than this." In the second, Joe tries to talk on the telephone to his son, who is in a box at the opera with the Health Secretary. "Does he like opera? Well why does he go then? Pharmaceuticals? Do they like opera?"

Both combine that very Bennettian sense of the distance that can open up between people when the habits of proximity and of shared values start to fade. This is what gives Allelujah! its emotional punch as much as its comic impact. He's careful not to make Gilchrist a monster; beautifully and warmly played by Findlay she is a humane woman whose rationalism has tipped over into a kind of inhumanity.

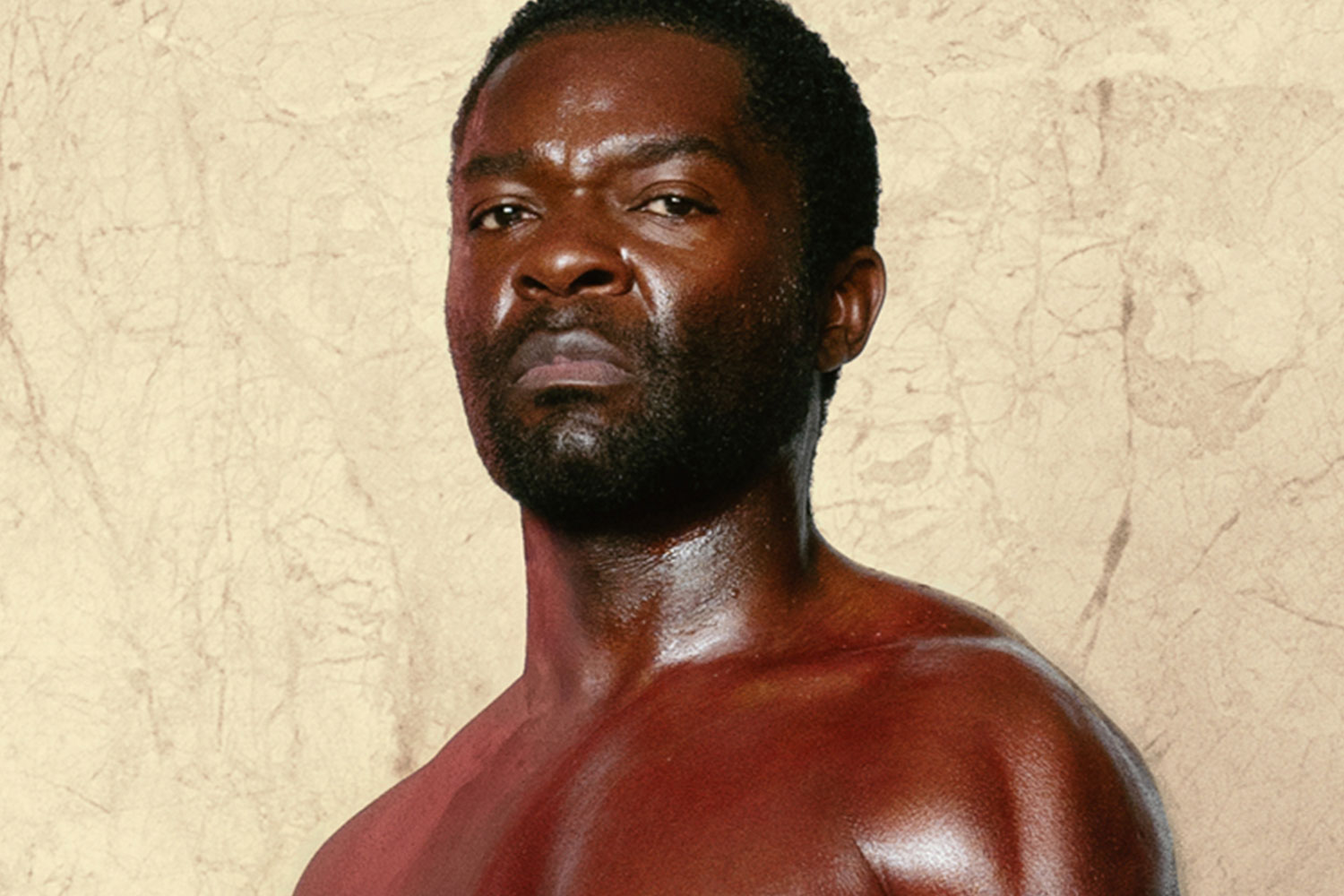

Bennett makes it clear too that he is worried that is where the entire country is heading; Valentine's final speech (delivered with subtle power by Sacha Dhawan) is a warning and a plea for exactly the warmth and empathy that this hugely enjoyable play provides.