The Artist review – from silver screen to stage spectacular

The world premiere production runs at Theatre Royal Plymouth until 25 May

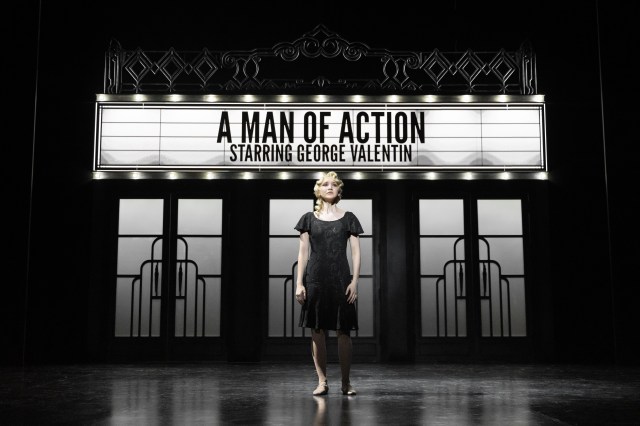

Michel Hazanavicius’s 2011 black and white, (mostly) silent movie won multiple Oscars, and was a valentine to old-school Hollywood and the art of filmmaking. Drew McOnie and Lindsey Ferrentino’s stage version is faithful to the spirit, the glamour, the grit and quirky humour of the original but turns it into a loving, exhilarating celebration of the wonders of the twin theatrical bedfellows of dance and storytelling through music. This iteration of The Artist is a magical piece of total theatre, defying generic classification (is it a ballet? is it a play? is it a musical? the answer to all these questions is basically yes) but one that for the most part works triumphantly on its own unconventional terms.

McOnie’s production is sleek, stylish, technically accomplished…and choreographed to within an inch of its life: furniture, cameras, screens, even Isaac McCullough’s four-piece band being moved around on platforms, swirl and glide across the stage as though in constant thrall to Terpsichore. The dancing itself is, as expected, terrific, with a cast featuring core members of McOnie’s regular company, and led by former New York City Ballet poster boy Robert Fairchild, best known over here for starring in the An American In Paris musical.

Fairchild inherits Jean Dujardin’s award-winning role of George Valentin, the movie star fatally unable to make the transition from silent pictures to the talkies, and delivers another masterclass in unforced charm and elegant athleticism. It’s hard to think of any other performer capable of simultaneously conveying vulnerability and physical might so effectively. Of course, when he dances it’s like muscular quicksilver, but it’s the acting choices that make this performance so affecting and memorable.

That vulnerability is crucial too: one significant tweak here from the source material is in the punching up of the female power in the story, and without Fairchild’s signature likability, the initially inflexible Valentin runs the risk of coming across like a reactionary, arrogant jerk. The heroine Peppy Miller (Briana Craig) has more agency in Ferrentino and McOnie’s version and isn’t pushy and ambitious just for herself as she forges a career in the male-dominated film industry, but for women in general. Significantly, the first spoken word in the whole evening comes from Peppy, approximately halfway through the 105-minute running time, and it’s “no” in response to yet another unreasonable request from a male director. It’s a quietly shocking moment of empowerment in a show that wears its forward-thinking agenda lightly, dressing it up in enchanting theatrical ingenuity and originality, but which never loses sight of the seriousness at its core.

Craig is a fabulous find. With her wig that’s a tumble of platinum curls, she sometimes bears an uncanny resemblance to the melancholic beauty of real silent movie star Mary Pickford, and she navigates with skill the fine line between Peppy’s go-getting chutzpah and her innate kindness. When she dances with Fairchild, their chemistry is joyous and palpable.

In a show that champions women, the female performers come off especially well. Rachel Muldoon brings fire and humour to a cranky silent screen siren forced to move with the times, and Ebony Molina finds a real, affecting gravitas to Valentin’s neglected, discontented wife. Tiffany Graves is a sassy knockout as a gossip columnist-cum-MC who’s anything but silent.

Gary Wilmot is a generally lovely stage presence but his cuddly joviality currently seems somewhat at odds with the bullying, film-making tyrant who turns on Valentin and gives Peppy so much to kick against. As with the original movie, the cheeky, faithful dog (now renamed Uggie in memory of the popular animal actor) all but steals the show. Here he’s a wonderfully expressive puppet, robustly but delicately manipulated by Thomas Walton, with a permanently wagging tail, a bemused expression and – when the show moves into sound – a shrill bark.

In an homage to the techniques of cinema, McOnie uses shrinking frames and screens to create the illusion of close-ups and to draw the eye. It’s visual storytelling raised to a fine art, but sometimes feels superior to the way the plot itself is laid out, at least at present. For instance, Peppy’s journey from enthusiastic wannabe to fully fledged star happens so quickly it’s almost whiplash-inducing, and the transition from a show conducted entirely in mime and dance, to musical numbers and dialogue could be sharper and more specific.

The colour pallet of Christopher Oram’s spare yet gorgeous designs is exclusively black and white, as befits the show’s milieu and, when another hue is allowed to bleed in, all we get, and all we need, is just a smattering of gold. Zoe Spurr’s lighting design complements this aesthetic exquisitely, and the video designs by Ash J Woodward, ranging from the entrancing to the nightmarish, are also wonderfully effective. Simon Baker’s imaginative manipulation of sound is equally essential and proves equally successful.

Simon Hale’s score is practically another principal character in the show, and a beautiful one at that. Referencing existing pieces such as Louis Prima’s “Sing Sing Sing” and Duke Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing” but featuring plenty of original composition, it’s propulsive and transporting, running the gamut from aggressive syncopation to dreamy escapism, and seamlessly supporting McOnie’s unique melding together of genuine drama and gorgeous flights of fancy. The musicians are superb and work tirelessly, although it would be even more satisfying if there were a few more of them.

If the written text is more efficient than inspired, it’s effective at establishing mood and character. Ferrentino has fun making wordplay out of Peppy and Wilmot’s Zimmer attempts to get George to find his voice, and when he does make the breakthrough, it’s genuinely affecting. That his real revelation is the joyful discovery of the noise a tap-shoed foot can make on a hard surface leaves us in little doubt as to where this production’s beating heart really lies.

McOnie’s work is endlessly pleasing to watch but here it’s infused with a surprisingly touching humanity that keeps at bay any suggestion that the final product is a victory of style over substance. The eye may be dazzled, but the heart and mind are engaged too. It’s also refreshing to see a piece of theatre with such a blatant and confident disregard for the traditional boundaries of genre, and one can only hope that this doesn’t impact on its commercial prospects moving forward. I doubt it will as, ultimately, The Artist is a rollicking good time. The Plymouth run is brief (it concludes this weekend) but I doubt this is the last we’ve seen of this unique show. It isn’t perfect…yet…but it has the makings of a big fat hit.